1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and Jus Soli Provisions

As stipulated in The Constitution of Tuvalu Bill (2022) enacted in September 2023, Tuvalu citizenship laws operate through both jus sanguinis and jus soli provisions. Regardless of birthplace, a child born to at least one parent who is a citizen of Tuvalu will be a citizen. Children born outside of Tuvalu to a Tuvalu citizen parent automatically acquire Tuvalu citizenship through jus sanguinis provisions. A child cannot gain citizenship by birth in the territory if neither parent is a citizen of Tuvalu. If the child’s father (not mother) is a foreign diplomat or a citizen of a country with which Tuvalu is at war, that child will not gain jus soli citizenship. Foundling children are in theory protected under Article 44(2), which states that foundlings discovered in Tuvalu will “be considered to have been born in Tuvalu”. However, there is no provision protecting such foundling children from becoming stateless as the child must have one citizen parent to gain citizenship by birth.

Neither the 2023 Constitution or the Citizenship Act specifically mention or give a definition for stateless persons or statelessness.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

The Citizenship Act provides that anyone who is “of full age and capacity” is eligible for citizenship through naturalization. The conditions for being granted a positive decision through this process are that the person has been “ordinarily resident” in Tuvalu for the past 7 years, intends to stay in Tuvalu permanently, can support themself financially, understands Tuvalu laws and customs, is not suffering from a permanent communicable disease, or any other conditions identified by the Citizenship Committee. The Act also states that foreign citizens applying for naturalization must renounce their prior citizenship before registering as a citizen of Tuvalu. The requirement to renounce foreign citizenship prior to applying for naturalization could cause some people in this process to become stateless if they are refused citizenship of Tuvalu after renouncing their foreign citizenship. Explicit protections preventing such instances from occurring should be included in the legislation. There are no provisions in Tuvalu’s national legislation providing a simplified procedure for stateless persons to acquire naturalized citizenship.

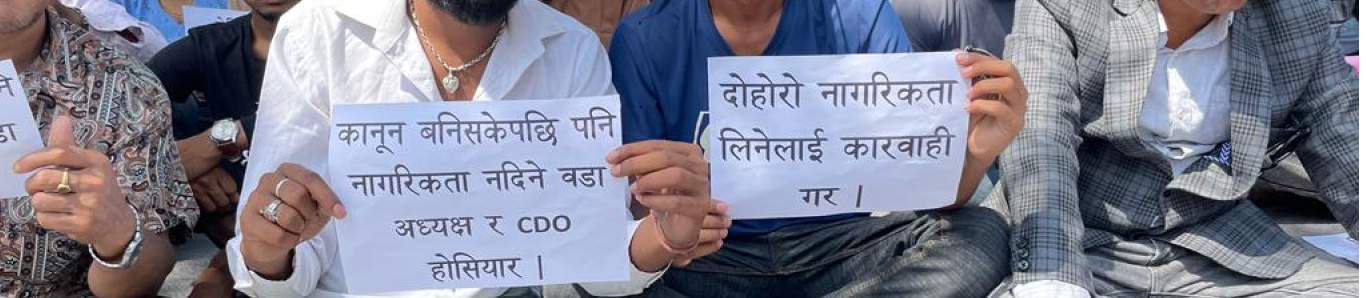

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in Tuvalu. While there is no provision explicitly stating this, the naturalization procedure in Article 6 of the Act includes a requirement to renounce prior citizenship in order to gain citizenship of Tuvalu. Article 10 of the Act provides some protections from statelessness for foreign citizens renouncing their citizenship in order to gain citizenship of Tuvalu. It states that if renouncing citizenship is “impracticable” or is not permitted by the other state of citizenship, the foreign citizen can instead make a declaration of intent to renounce the other state’s citizenship and do so within a defend period after receiving Tuvalu citizenship. This ensures that foreign citizens going through this process do not become stateless in the process of application for Tuvalu citizenship and renunciation of other citizenship.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

The only international treaties ratified by Tuvalu are the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, the CRC, and CEDAW. Of which, Tuvalu has made no reservations.

The CEDAW Committee has previously expressed concerns on the increasing possibility of statelessness in Tuvalu as a result of climate change.1818 Increasing rates of emigration to neighboring countries has increased the risk and reality of displacement which can lead to statelessness. It was recommended that Tuvalu develop a mitigation strategy for displacement and proactively address the potential statelessness that could arise from it. It was further recommended that Tuvalu “ensure that women, including those living on the outer islands, are included and may actively participate in planning and decision making processes concerning their adoption”. Tuvalu was issued two reminders by the Rapporteur in 2017 to provide follow-up information on how they have been working on these recommendations, but Tuvalu has yet to provide this information. However, in the new Constitution enacted in 2023, a new definition of statehood was established for Tuvalu in light of the existential threat of climate change. The Constitution provides that the state’s physical territory will remain the same, regardless of rising sea levels, and establishes the country’s intention for “responding to climate change, which threatens the security and survival of its people and its land”.

In 2020, concluding observations by the CRC Committee noted concerns about low birth registration in the country, in particular in the outer islands. The Committee recommended ensuring that everyone has access to birth registration, especially in the outer islands and for children of unmarried parents. It was further recommended to remove the requirement of registration fees for late birth registration. In the 2023 UPR session, Tuvalu provided that every newborn in the country is “required to be registered either at the General Registrar Office or with Local Government for those in the outer islands ”and that a list of new born babies must be sent to the Register General every 3 months. As a party to CRC, Tuvalu is bound to ensure that every birth in the territory is registered immediately to prevent statelessness.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuvalu |