1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis Provisions

The Constitution of the Independent State of Papua New Guinea (1975) provides that citizenship eligibility operates through a jus sanguinis structure. A child born in the territory to at least one citizen parent will be a citizen according to Article 66(1) of the Constitution. If a child is born outside of Papua New Guinea (PNG) to at least one citizen parent, their birth must be registered to be considered a citizen. Papua New Guinea’s Constitution provides foundlings automatic access to citizenship by descent by deeming them the be the child of a Papua New Guinean citizen. There is no definition of a stateless person included in the Constitution. Further, PNG’s legislation lacks a statelessness determination procedure for identifying stateless persons in the context of migration. For non-refugee stateless persons, there are no existing legislative provisions to provide local residence.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

There is a naturalization process available for those who wish to become a citizen of Papua New Guinea with a simplified procedure available for those who are Papua New Guinean descendants and who have married a Papua New Guinean spouse. The standard naturalization process requires that the individual have resided in the country for eight years, be of good character, intend to continue residing in the country, speak and understand Pisin or Hiri Motu or a vernacular of the country, among other eligibility requirements. There is no explicit mention of a simplified or expedited procedure for stateless persons to apply for naturalization in the Constitution.

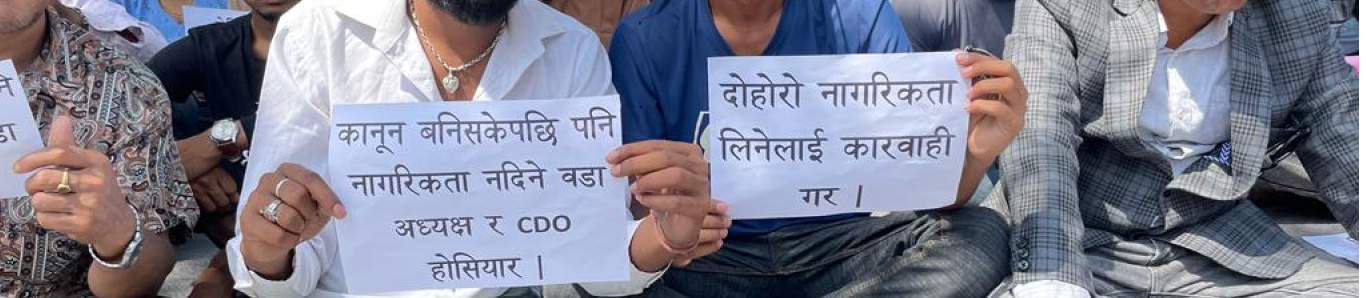

c. Dual Citizenship

According to Article 64 of the Constitution, dual citizenship is not recognized, although there is an application process for getting dual citizenship approved by the Minister in special cases. A citizen of Papua New Guinea may not renounce their citizenship unless they already hold citizenship of a different country or are doing so in order to gain citizenship elsewhere.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

While Papua New Guinea has not ratified either the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons or the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, it has ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, the ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW. In regard to Article 4 of the ICERD, Papua New Guinea made a reservation that the scope of the country’s obligations to Article 4 may not go beyond the Constitution.

Papua New Guinea also made reservations on Articles 17(1), 21, 22(1), 26, 31, 32, and 34 of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Of particular note, the reservations on Article 17(1), 21, and 22(1) entail that Papua New Guinea is not obligated to ensure equal treatment to refugees as foreign nationals, aliens (with respect to housing), or nationals (with respect to elementary education). Reservations made on Articles 26, 31, and 32 allow that Papua New Guinea is not obligated to ensure freedom of movement for refugees, to ensure that refugees illegally residing in the territory are not issued penalties or movement restrictions, or to ensure that refugees are not expelled from the country without securing entry to another country. Further, the reservation on Article 34 stipulates that Papua New Guinea is not obligated to facilitate assimilation and naturalization of refugees. In the 2010 UPR submission for Papua New Guinea, it was recommended that the country remove the reservation on Article 34, provide citizenship to children born to refugees who would otherwise be stateless, and waive the citizenship application fee for refugees to gain PNG citizenship.

In the 2010 concluding observations, the CEDAW Committee expressed concerns regarding birth registration. The concerns were that despite the presence of a compulsory birth and marriage registration programme, there was still only a small percentage of the population registering births. The Rapporteur sent Papua New Guinea two reminders to provide follow-up information regarding these concluding observations, but none were received. Such concerns on strengthening and raising the level of birth registration have been further voiced in the second and third UPR which recommended the complete implementation of the Child Protection Act (2015) to prevent abuse and exploitation of children.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papua New Guinea |

3. Papua New Guinea’s Pledges to End Statelessness

In 2011, Papua New Guinea pledged to amend its legislation to be able to remove the reservations made to the Refugee Convention. It also pledged to facilitate access to naturalization of “West Papuan and other refugees by either waiving all fees or introducing a nominal fee only for applications for citizenship by refugees”. Since 2011, PNG has removed all seven reservations on the Refugee Convention in relation to refugees transferring from Australia, leaving room for legislative improvement in other contexts. As mentioned in the 2016 UPR submission, PNG has also reduced the fees for citizenship applications for all refugee applicants. For West Papuan refugees, the fee has been waived entirely.