1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis Provisions

The citizenship law of Nauru operates through jus sanguinis provisions with a child born either within or outside of the country to at least one Nauruan citizen will be granted citizenship, as provided by the Citizenship Act of 2017. The Act also includes a provision providing automatic citizenship to “a person born in the Republic on or after 31 January 1968” if they would otherwise be stateless. In 2017, Nauru amended their citizenship laws to remove gender discriminatory provisions that had limited the ability of women to pass on their citizenship to a spouse. There is no definition of statelessness or explicit mention of statelessness in Nauru’s national citizenship legislation.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

An application for citizenship is available to anyone who is 20 years of age and pays the application fee. Decisions on naturalization applications are final and there explicitly no methods of appeals or reviews by the Court. Citizenship by application may be given to a person born in the Republic to parents who are not citizens and the person has resided in the country continuously for 20 years. There is no simplified or expedited procedure for refugees and stateless persons.

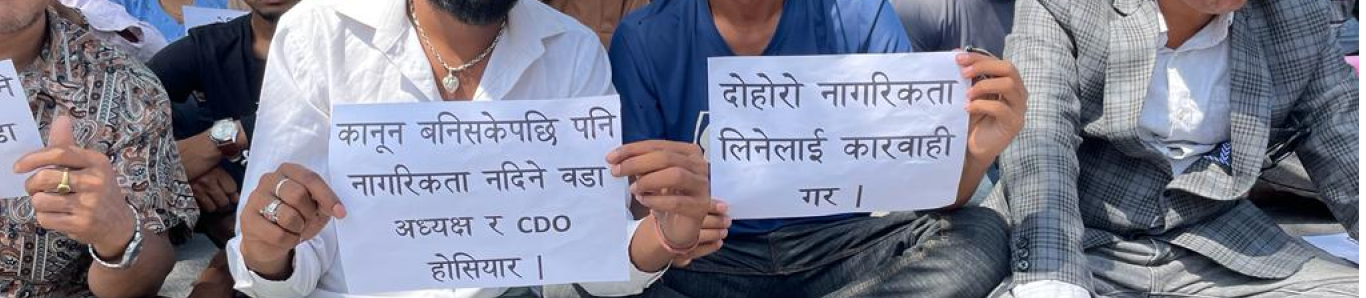

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is recognized in Nauru.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

Nauru has acceded to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, the CRC, and CEDAW with no reservations. In its 2016 concluding observations, the CRC Committee expressed concerns regarding the inhumane treatment of refugee and asylum-seeking children, including those who are unaccompanied, sent from Australia for offshore processing. While there are some legislative safeguards against statelessness for children in Nauru, UNHCR in 2015 expressed concerns in the recent UPR submission that there are no safeguards for foundling children. Nauru’s national citizenship legislation does not include a provision which grants citizenship to foundlings. UNHCR recommended that Nauru amend legislation to ensure that foundling children in the territory are presumed to be a national of Nauru. In 2021, in the 3rd cycle of UPR, the State was asked to introduce provisions in the Constitution to end “statelessness of abandoned minors and the loss or stripping of nationality”.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nauru |