1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and Jus Soli Provisions

Vietnamese citizenship law operates through a jus sanguinis structure, providing that children born to two citizen parents are considered citizens whether born within or outside the country. Where a child has a single Vietnamese parent, regardless of whether the other parent is a foreign citizen, is unknown, or is stateless, the parents must provide a written statement upon birth registration for their child to gain Vietnamese nationality.

Children may gain jus soli citizenship if:

- One of the parents is Vietnamese, the other is a foreigner and the two parents cannot reach an agreement on the citizenship for the child upon birth registration;

- Both parents are stateless but have permanent residence in Viet Nam; or

- The mother is stateless but has permanent residence in Viet Nam and the father is unknown.

- Foundlings are also eligible for citizenship by birth.

Viet Nam’s citizenship legislation defines a stateless person as “a person who has neither Vietnamese nationality nor foreign nationality”, which is consistent with the definition in the 1954 Convention on the Status of Stateless Persons.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

A foreigner or a stateless person who has permanent residence in Viet Nam is eligible to apply for Vietnamese nationality if they have resided in Viet Nam for five years, are financially independent, have capacity to exercise full civil act rights and can integrate into the Vietnamese community, among other requirements. A simplified naturalization procedure is available for applicants who are the spouse, natural parent, or natural offspring of Vietnamese citizens or have made a significant contribution to Viet Nam. One must have a Vietnamese name to apply for naturalization in Viet Nam, which can be selected by the applicant. Stateless persons are eligible for a simplified process, where they may apply for naturalization without adequate personal identification papers if they have resided in Viet Nam for at least 20 years by 2009, when the new law became effective.

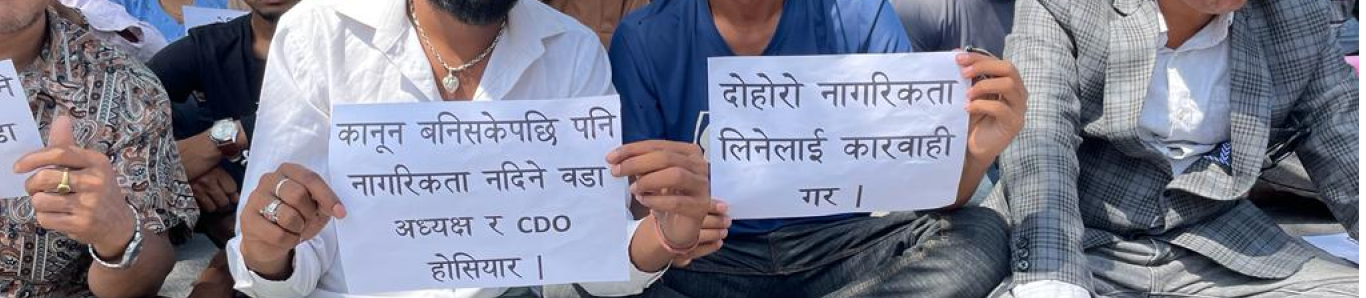

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is only recognized in some cases. Dual citizenship is permitted for a person who is a spouse, a natural parent, or natural offspring of Vietnamese citizens. Those who have made meritorious contributions to Viet Nam’s development and defense, or have outstanding talents that will be useful for Viet Nam are eligible to keep their prior citizenship after being granted naturalized citizenship. Naturalized citizens who are not eligible to retain prior citizenship must renounce such citizenship.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

While Viet Nam is yet to ratify the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, and the 1951 Refugee Convention (and its 1967 Protocol), it has ratified ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations.

In its 2014 concluding observations, the CESCR Committee expressed concerns regarding children of returned marriage immigrants in Viet Nam who remain stateless and unable to access education and other services. The Committee recommended that Viet Nam “recognize and register children of marriage immigrants who are currently stateless”. Due to its ratification of ICESCR, Viet Nam is obligated to protect freedom from discrimination, including on the grounds of nationality.

The 2015 concluding observations by the CEDAW Committee included concerns over the 800 stateless women who lost Vietnamese citizenship as a result of failed attempts to acquire a different nationality. However, Article 23 of the Law on Vietnamese Nationality provides that anyone who has renounced Vietnamese citizenship to gain citizenship elsewhere is eligible to reacquire Vietnamese citizenship and many of these women have been able to do so.

Concluding observations by the CRC Committee in 2022 recommended that Viet Nam develop a procedure to determine the stateless status of children as well as work towards universal birth registration by raising public awareness of the importance of birth registration. As a party to CRC and ICCPR, Viet Nam is obligated to ensure the right to acquire nationality as well as that every birth in its territory is registered immediately. Further, Article 2 of the Law on Vietnamese Nationality provides that in Viet Nam every individual has the right to nationality. Article 8 further provides that Viet Nam enables children born in the territory of Viet Nam to have nationality and stateless people permanently residing in Viet Nam to acquire Vietnamese nationality in accordance with applicable law.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vietnam |