1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and Jus Soli Provisions

Singaporean citizenship legislation, covered by the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore, operates mostly through jus sanguinis principles with some differentiation between persons born within or outside of the state. Individuals born in Singapore are considered citizens by birth if at least one of their parents is a citizen of Singapore. Children born to two parents who are not citizens of Singapore will not be citizens; however, eligibility in this case can be left to the discretion of the government. Foundlings are considered to be Singaporean citizens at birth. There is no definition or explicit mention of a stateless person or statelessness in the citizenship legislation of Singapore.

Citizens are able to confer their nationality to their children even if their child is born outside of the territory of Singapore. However, children born outside of Singapore are considered citizens by descent and can only acquire citizenship of Singapore if either of their parents is a citizen by birth, by descent, or citizens by descent who have met certain residence requirements. Prior to a 2004 amendment to the Constitution, citizenship by descent could only be conferred by the father of a child, who was himself a citizen by birth or registration, not descent. Additionally, the births of children outside of Singapore must be registered before they gain Singaporean citizenship by descent, and such children will cease to be citizens if they do not take Singapore’s Oath of Renunciation, Allegiance and Loyalty within one year of their 21st birthday.

It is important to note that Singapore’s citizenship legislation still contains some gender-discriminatory provisions. The law provides that children born in Singapore whose father (not mother) is a foreign diplomat or enemy alien (and the birth occurred during the occupation from that enemy state) are not considered citizens by birth even if their mother is a citizen of Singapore. Singaporean citizenship law further limits the ability of married women to confer their nationality onto foreign spouses on the same basis as men.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

Foreigners or stateless persons may gain Singaporean citizenship by registration, which is different from the process of naturalization. Any foreigner of 21 years or more may apply and be registered as Singaporean citizen if the government is satisfied of their good character, of their meeting certain past residence requirements (in practice, having been a Permanent Resident of Singapore for at least two years), of their intention to reside permanently in Singapore, and of their elementary knowledge of one of the country’s four official languages. There is a simplified procedure for the acquisition of citizenship by registration for foreign women married to a Singaporean citizen.

Foreigners and stateless persons are able to apply for citizenship by naturalization through a more stringent process than that afforded to citizens by registration. If the government is satisfied that the applicant is of good character, they meet more stringent past residence requirements, they intend to reside permanently in Singapore, and they have adequate knowledge of the national language (Malay), the applicant will be granted naturalized citizenship. No simplified or expedited process of either citizenship by registration or by naturalization is available for stateless persons or refugees.

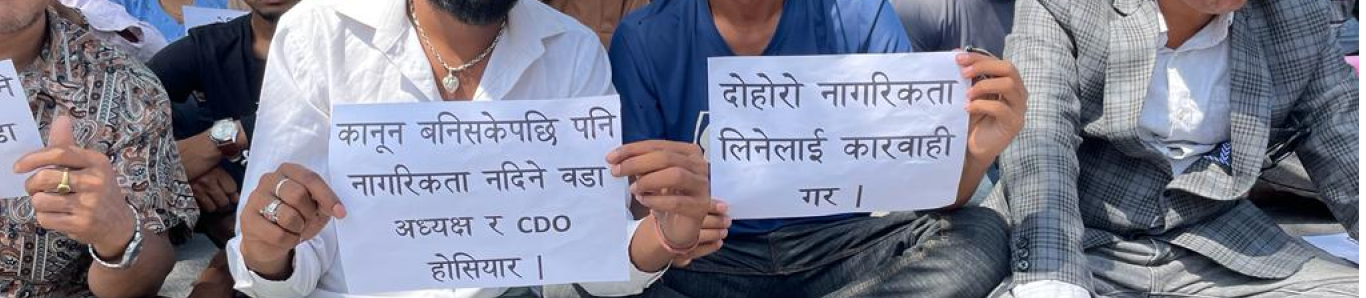

c. Dual Citizenship

Whilst Singaporean citizens also enjoy the status of citizens of the Commonwealth, Singapore does not recognise or accept dual citizenship for its citizens. A child born of Singaporean parents outside of Singapore must renounce any jus soli rights to citizenship in the country of their birth if they want to become a citizen by descent. Any citizen of 21 years or more may renounce their citizenship if they are also citizens of another state or are about to become so. Further, the government may deprive a Singaporean citizen of their citizenship upon their acquisition of foreign citizenship or on their exercise of certain rights as foreign citizens, such as the use of a foreign passport or the exercise of their voting rights.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

To date, Singapore has ratified ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW. Singapore is not party to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, or the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. In addition, Singapore is one of 13 UN states which have not signed or ratified either the ICCPR, or ICESCR. Singapore has signed the non-binding ASEAN Human Rights Declaration, as one of the ten countries that drafted and adopted it in 2012.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singapore |

One of Singapore’s notable reservations on the ICERD is that it reserves the right to “apply its policies concerning the admission and regulation of foreign work pass holders, with a view to promoting integration and maintaining cohesion within its racially diverse society”. The effect of this reservation can be seen in the fact that one’s nationality can directly affect one’s eligibility for specific forms of immigration to Singapore. In 2022, the CEDAW Committee in its concluding observations raised concerns which stated that “insufficient measures have been taken to reduce wage discrimination based on nationality”. It was recommended that Singapore ensure that employment restrictions on workers’ countries of origin do not constitute discrimination based on nationality as well as work “to eliminate wage discrimination based on nationality”. The Committee also urged Singapore to ensure comprehensive data collection for ethnic groups, including non-citizens such as migrants, refugees and stateless persons. By ratifying the ICERD, Singapore has committed to ensuring non- discrimination on the basis of nationality and the right to a nationality.

Further concerns were expressed regarding lack of legal safeguards against childhood statelessness to which Singapore was recommended to amend its citizenship legislation to ensure that children who would otherwise be stateless are granted Singaporean nationality. These concerns were echoed by the CRC Committee in 2019, which recommended that Singapore amend Article 122 of the Constitution in order to ensure no child is or becomes stateless. As a party to CRC, Singapore is obligated to ensure that no child is left stateless. However, one relevant reservation Singapore made in its ratification of CRC argues that Singapore’s national law sufficiently protects children’s rights, meaning that Singapore will not accept any obligations beyond those prescribed in its Constitution. This has been criticised by other State parties as well as the CRC Committee. The Committee added that in order to eliminate discrimination towards children without Singaporean citizenship, Singapore should adopt a comprehensive strategy to end discrimination towards children, including by collaborating with mass media, social networks, and community leaders to change dominating discriminatory attitudes.

In 2017, the CEDAW Committee recommended that Singapore publish updated statistics on the number of stateless persons in the country as well as to ensure that children born in the territory who would otherwise be stateless be granted citizenship, echoing concerns expressed in concluding observations made by the CRC Committee and the CERD Committee. Although Singapore reduced the number of reservations made to CEDAW in 2011, reservations remain in relation to Article 2. Crucially, Article 2 commits states to take steps to eliminate all discrimination against women through anti- discrimination laws, public institutions and tribunals, and repeal all discriminatory provisions of domestic legislation. As a result of these reservations, the UN Committee which oversees the Convention has stated that the reservations are “impermissible since these articles are fundamental to the implementation of all the other provisions of the Convention”.

Source: ReImagining Singaporeans, ‘Handbook on Statelessness in Singapore’

In the 2022 UPR submission for Singapore, the High Commissioner for Human Rights highlighted the need to ensure that children born in Singapore who cannot acquire another nationality are able to automatically acquire Singaporean nationality.