1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis Provisions

The citizenship law of the Philippines operates through a jus sanguinis structure with children born to a citizen parent or parents within or outside of the territory considered citizens.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

In March 2022, the Supreme Court of the Philippines introduced a new policy to facilitate and streamline the naturalization of stateless persons and refugees, an act supported by several UN agencies and representatives. The Rule on Facilitated Naturalization of Refugees and Stateless Persons, the first of its kind in the world, provides both a simplified and expedited naturalization procedure for stateless persons and refugees. Included in the Rule are provisions ensuring protection against discrimination for refugees and stateless persons and protecting family unity of refugees and stateless persons. A stateless person or refugee is eligible to apply for naturalized citizenship through this process if they have resided in the Philippines for at least 10 years, are financially stable, of good moral character, and can speak and write in one of the principal Philippine languages. Under the Rule, a joint petition may be filed by a refugee or stateless person together with his or her spouse and children. The Rule also provides that unaccompanied minors may apply for citizenship with the aid of governmental agencies, such as the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) or other relevant agencies. This is in line with the Philippines’s commitment to uphold children’s right to nationality under international agreements. It appears that no petition has yet been filed under the Rule as of May 2022, but it is said that more than 800 people are expected to benefit from it.

A reduced period of five years is available for those who are married to a Filipino, have introduced a new industry or invention to the Philippines, are a school teacher for at least two years, or were born in the Philippines. A person may be disqualified from this process if they are opposed to organized governments, endorse violence, are a polygamist, convicted of a morally compromising crime, suffering a “mental alienation or incurable contagious diseases”, have not socialized with Filipinos during their residence, or are a subject of a nation with which the Philippines is at war. Documents required for the application include a birth certificate, marriage certificate (if applicable), proof of recognition of refugee or stateless status, a moral endorsement from two Philippine citizens, among others.

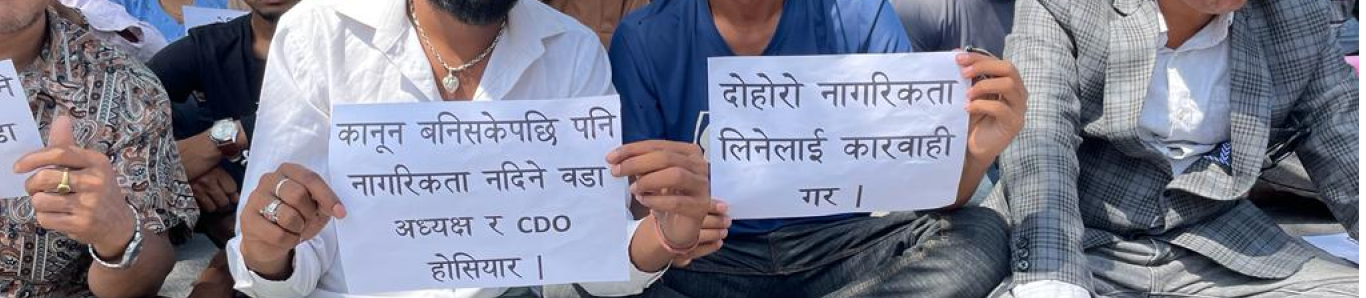

c. Dual Citizenship

The right for Philippine citizens to maintain dual citizenship is available only to natural-born citizens who have earlier lost their Philippine citizenship by reason of acquisition of foreign citizenship. While the renunciation process for foreigners is not stipulated in legislation, the oath to be taken upon issuance of Certificate of Naturalization states that the foreign citizen relinquish allegiance to any foreign state.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

Following accession to the 1961 Statelessness Convention in March 2022, Philippines is the only country in Southeast Asia and one of only three countries in the entire Asia-Pacific to be party to all the relevant Statelessness, Refugee and Human Rights Conventions. While it is commendable that the Philippines has ratified all treaty bodies relating to statelessness, reservations were made to the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons. The reservations are on Article 17(1), which ensures stateless persons equal rights as aliens in wage- earning employment and Article 31(1), which protects stateless persons lawfully residing in the territory from expulsion unless for national security reasons. On this, the Constitution disallows stateless persons from practicing their profession in the Philippines under the provisions which states, “the practice of all professions in the Philippines shall be limited to Filipino citizens”.

In 2023, the CERD Committee included in its concluding observations concerns over the “lack of comprehensive and reliable publicly available statistics on demographic composition of the population”, including for stateless persons. Further, the Committee also highlighted the concerning absence of protective legislation against statelessness, particularly regarding “unregistered children living in the context of forced displacement”. It was recommended that the Philippines improve civil and birth registration mechanisms in geographically remote and conflict-affected areas. In 2016 concluding observations by the CESCR Committee, the Committee expressed concerns regarding the lack of birth registration of indigenous children, Muslim children, and children of overseas Filipino workers. These concerns were echoed in the 2022 concluding observations by the CRC Committee, which expressed that while these affected children remain unregistered, they are at risk of “statelessness and deprivation of the right to a name and nationality and of access to basic services”. As a party to the CRC, the Philippines is obligated to ensure that every child’s birth is registered immediately as well as to ensure all children the right to acquire a nationality.

The Rule on Facilitated Naturalization of Refugees and Stateless Persons defines a stateless person as “a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law,” which is directly aligned with the definition included in the 1954 Convention on the Status of Stateless Persons. The Philippines is one of few countries in the entire Asia-Pacific region to have implemented a statelessness determination procedure having established the procedure in 2012. The Philippines introduced a National Action Plan to End Statelessness in 2015 based on UNHCR’s Global Action Plan to End Statelessness. Further, the Philippines declared the years 2015 to 2024 as the “Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) Decade” as well as committed to universal birth registration.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philippines |

In the Plan, the Philippines shared its intentions to abide by the following action points:

- Resolve existing situations of statelessness;

- No child is born stateless;

- Remove gender discrimination from nationality laws;

- Grant protection status to stateless migrant and facilitate their naturalization;

- Ensure birth registration for the prevention of statelessness;

- Accede to the UN Statelessness Conventions;

- Improve quantitative and qualitative data on stateless populations.