1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis Provisions

Citizenship of Myanmar, stipulated by the Burma Citizenship Law, is defined largely upon ethnic ground, and through jus sanguinis principles, with citizenship available to those who are considered “nationals” or whose parents both are nationals. Article 3 states that members of the Kachin, Kayah, Karen, Chin, Burman, Mon, Rakhine or Shan and ethnic groups who have resided in Myanmar since 1823 are Burma citizens. Article 4 further provides that “the Council of State may decide whether any ethnic group is national or not”. Myanmar’s citizenship legislation does not include a definition of a stateless person nor does it explicitly mention or address statelessness.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

The citizenship legislation of Myanmar provides for two other categories of citizenship: associate citizenship and naturalized citizenship, which the government may confer on any person ‘in the interest of the State’. Citizenship by naturalization is only available to those with at least one citizen parent or who can prove sufficient links to the country at the time of its independence. While this may offer a way for persons outside of the designated ethnic groups to acquire citizenship in Myanmar, citizenship acquired by naturalization does not provide the same quality and security of citizenship as is granted to indigenous groups. For example, an associate or naturalized citizen’s citizenship may be stripped or they may be blocked from enjoying certain rights available to citizens of the designated ethnic groups. This distinction between citizens contradicts Article 21(a) of the 2008 Constitution, which states that “every citizen shall enjoy the right to equality.” There is no scope in the legislation for naturalization through marriage or long-term residence. Stateless persons are not eligible for naturalization in Myanmar.

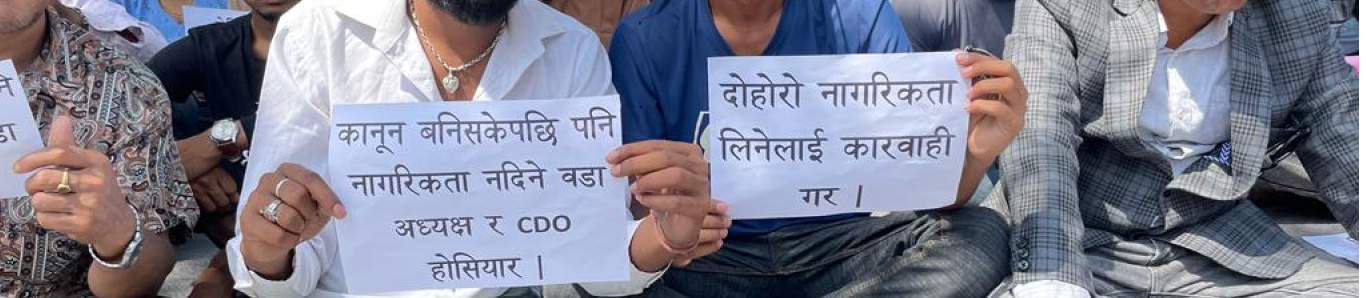

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not permitted in Myanmar. Foreign citizens applying for naturalization must renounce prior citizenship upon acceptance to citizenship of Myanmar.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

Myanmar has only ratified three relevant treaty bodies, that includes ICESCR, CRC and CEDAW. In its 2012 concluding observations, the CRC Committee expressed concerns regarding the large portion of the population without access to citizenship, the lack of protective legislation for stateless children and the overall strict citizenship laws which leave many stateless. The Committee was also concerned that ethnicity and religion are marked on identity cards, exposing minority populations to discrimination. The large number of children, particularly Rohingya children, whose birth remain unregistered was also noted, citing multiple administrative barriers to registration. It was recommended that Myanmar remove such barriers and ensure effective registration of all children in the territory. As a party to the CRC, Myanmar is obligated to ensure that every child’s birth is registered immediately as well as that all children enjoy the right to acquire a nationality.

In its 2019 concluding observations, the CEDAW Committee also raised extreme concern over the repeated warnings given to Myanmar regarding its regressive Citizenship Law and ‘citizenship verification’ exercises conducted in northern Rakhine State. These verification exercises have resulted in the “arbitrary deprivation of nationality and statelessness of Rohingya women and girls”. Further, Rohingya women and girls who refuse to identify as ‘Bengali’ are “ arbitrarily excluded from the verification process”. The Committee recommended that Myanmar amend its discriminatory laws on citizenship, ensure the registration of Rohingya children, and recognize Rohingya individuals’ and communities’ right to self-identify.

In Myanmar’s Universal Periodic Review, the 1982 Citizenship Law was identified to be discriminatory on the grounds of race, placing several groups, including the Rohingya, at risk of statelessness. The UPR further adds that while groups outside of the 135 listed ethnic groups in citizenship legislation may be eligible for citizenship under certain provisions, implementation has been arbitrary and discriminatory.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myanmar |

3. Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

In 2019, The Gambia filed a case against Myanmar in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) accusing Myanmar of violating the 1948 Genocide Convention and its intention to “destroy the Rohingya as a group”. The Gambia also requested that the Court grant measures to protect the Rohingya from the ongoing genocide. Albeit Myanmar denied these allegations, the ICJ ruled in 2020 that Myanmar is now legally bound to “take measures to protect the Rohingya from genocide; prevent the Military from committing genocide; take steps to prevent the destruction of evidence of genocide; and file a report with the ICJ in four months, and every six months that follow until the closure of the case, documenting what they have done to ensure these measures are met”.

Objections by the Myanmar government in 2021 that the Court did not have jurisdiction for the case were thwarted by the Court’s judgement in 2022. In 2002, a rare occurrence for the U.S., Anthony Blinken, U.S. Secretary of State, explicitly stated that the Rohingya have, in fact, been subjected to crimes against humanity constituting genocide by the State of Myanmar, essentially expressing its support for the Gambia’s case. The U.S.’s statement is said to be based on the findings of experts appointed by the U.S. State Department which supports the findings of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar. On November 15, 2023, the United Kingdom, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, and the Netherlands filed a joint declaration of intervention, supporting the accusations that Myanmar’s systematic ‘clearance operations’ amount to acts of genocide intended to destroy the Rohingya as a group. A separate declaration of intervention was received by the ICJ from the Maldives on November 10, 2023. The ICJ has set May 2024 and December 2024 as time limits for written pleadings from The Gambia and Myanmar respectively.

Albeit Myanmar denied these allegations, the ICJ ruled in 2020 that Myanmar is now legally bound to “take measures to protect the Rohingya from genocide; prevent the Military from committing genocide; take steps to prevent the destruction of evidence of genocide; and file a report with the ICJ in four months, and every six months that follow until the closure of the case, documenting what they have done to ensure these measures are met”.