1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis Provisions

Citizenship legislation of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) operates through jus sanguinis provisions, as stipulated by the Law on Lao Nationality (2004). Lao citizenship provides that children born to two citizen parents are considered citizens regardless of their birthplace. When a child has a single Lao parent and is born in Laos they will gain automatic citizenship by descent; however, if born outside of the country, at least one parent must be a permanent resident in order for the child to gain Lao citizenship.

While Laos’s citizenship legislation does not include a definition of statelessness specifically, it uses the term ‘apatride’, translated from Lao, which constitutes an individual residing in Laos who is not a Lao citizen and who is unable to certify their nationality, which can be interpreted as stateless persons or persons with undetermined nationality. This does not align with the definition provided by the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, which determines the status of a potential stateless person by referring to national legislation on the citizenship of the country the person has or had ties with.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

Foreigners and ‘apatrides’ can gain Lao citizenship by request. To be eligible, the applicant must be continuously resident in Laos for at least ten years, relinquish prior nationality, be able to speak, read, and write fluently in Lao, and be financially independent, among other requirements. While stateless persons and refugees may be eligible for this process, there is no simplified or expedited process of naturalization available to them.

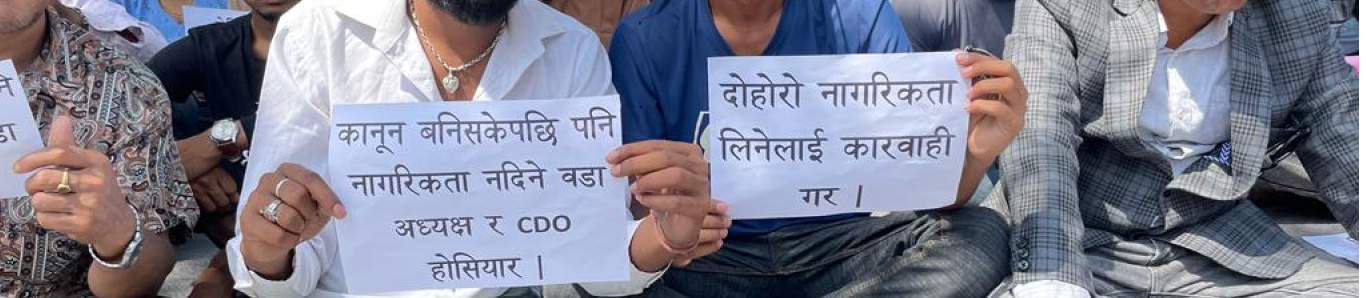

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is only recognized for those of Lao race who acquire citizenship by request. In order to do so, a person who has a prior nationality must be a permanent resident in Laos for 5 years. Lao citizens applying for citizenship elsewhere must first renounce their Lao citizenship. Similarly, a foreign citizen applying for Lao citizenship must agree to renounce their other citizenship. This could lead to temporary statelessness if the applicant’s citizenship application is denied after they have renounced their other citizenship. However, the foreign citizen could re-acquire their former citizenship if the law of the former country allows them to.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

While Laos has ratified the ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations, the country has yet to ratify the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, and the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

In 2018, the CRC Committee in its concluding observations expressed concerns regarding the fact that 75% of children under five years of age are unregistered and that only 33% of children have a birth certificate. The Committee identified that costs of registration are a barrier to universal birth registration and that children in rural areas have disproportionately lower access to birth registration. It was recommended that Laos raise awareness of the importance of birth registration.

To improve birth registration, Laos has been recommended to raise awareness of birth registration, establish a mobile registration system, and eliminate costs associated with birth registration. In 2018, the CEDAW Committee also cited concerns over the country’s low birth registration rate, especially in rural areas and among ethnic minority groups. By ratifying the CRC, Laos has committed to ensuring that all births are registered immediately and that all children have the right to acquire a nationality.

The Human Rights Committee, in its concluding observations, has raised concern regarding the enforced disappearances of members of the Hmong ethnic minority community, who were forcibly returned to Laos from Thailand in 2009.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic |