Laws

Citizenship Law

Jus sanguinis and jus soli provisions

Indonesian citizenship law operates through a jus sanguinis structure, stipulated by the Law of the Republic of Indonesia on Citizenship of the Republic of Indonesia (2006) (‘Law on Citizenship’), providing that children born to a citizen parent or parents within or outside of the country will be considered a citizen. Children born in Indonesia to an Indonesian mother, even if the father is stateless or from a country that does not grant citizenship to such children, are also considered as Indonesian citizens. Further, children born out of wedlock to an Indonesian mother or acknowledged by an Indonesian father before they turn 18 or married can be granted Indonesian citizenship. Indonesia lacks a definition of a stateless person in its citizenship legislation.

Indonesia also uses a restricted jus soli principle for certain cases of citizenship acquisition. Children born in Indonesia when their parents’ citizenship status is unclear, newborn children found in Indonesia with unknown parents, and children born in Indonesia when both parents lack citizenship or their existence is unknown can also obtain citizenship by birth. Lastly, children born outside Indonesia to Indonesian parents in countries granting citizenship and those born to parents whose citizenship applications were approved but one parent passes away before taking an oath or declaring allegiance can also be considered Indonesian citizens.

Naturalized citizenship

There is a naturalization process available for those who are 18 or are married, have resided in Indonesia for five consecutive years or ten years intermittently, are physically and mentally healthy, able to speak the Indonesian language, have a steady income, do not have prior citizenship, and have not been convicted of a criminal offense amounting to one year or more imprisonment. A stateless person may be eligible for this procedure if they meet these requirements; however there is no simplified or expedited procedure available to stateless persons and refugees.

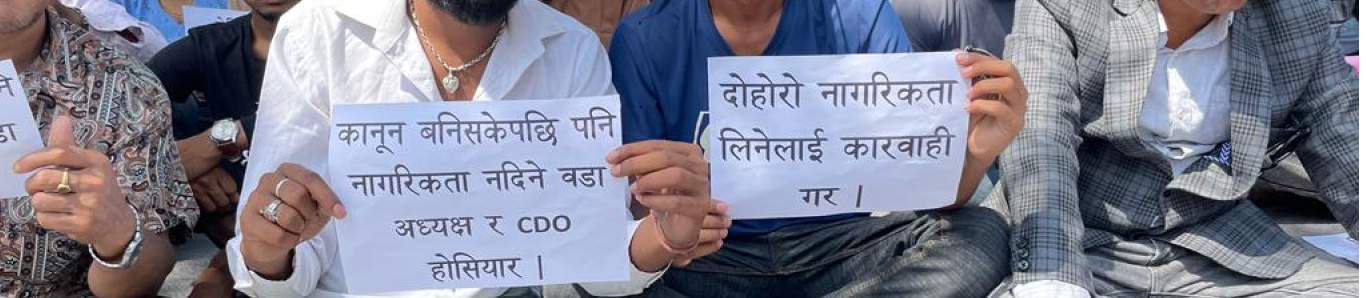

Dual citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in Indonesia. Foreign citizens applying for naturalization must renounce their prior citizenship upon acquiring Indonesian citizenship. Citizens of Indonesia may lose their citizenship through renunciation or through the acquisition of another foreign citizenship. Though there are exceptions for children under the age of 18 to maintain dual citizenship, due to the principle of jus soli which applies birthplace as the determining factor of citizenship, once the child reaches the age of 18, they must choose one citizenship.

Treaty ratification status

While Indonesia has not yet ratified the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, or the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, it has ratified the ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, CEDAW with no relevant reservations.

In 2014, the CRC Committee expressed concerns in its concluding observations regarding the requirement of indicating a child’s religion on their identity card, which could lead to discrimination, as well as the risk of statelessness for children born in the territory to two foreign parents who are not eligible for nationality elsewhere. In its 2022 concluding observations, the CEDAW Committee noted concerns over Article 41 of the Law on Citizenship, which “excludes children who were born to an Indonesian and a non-Indonesian parent before 2006 from obtaining Indonesian nationality”. It was recommended that Indonesia amend this provision to ensure that nationality is conferred to children in this scenario. As a party to the ICCPR, Indonesia is obligated to ensure the right to acquire a nationality.

Further, the Committee on Migrant Workers recently expressed concern regarding a large number of unregistered births of Indonesian migrant workers abroad, particularly those born out of wedlock, which it attributed to lack of information, bureaucratic obstacles and financial barriers.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indonesia |

✅ Signifies that the country is a party to the convention

⛔ Signifies that the country is not a party to the convention

Stateless 1 – 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons

Stateless 2 – 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness

Indonesia’s Pledges to End Statelessness

At the High-Level Segment on Statelessness in 2019, Indonesia pledged to:

- increase the scope of operation and the provision of infrastructure related to its national citizenship registry;

- increase the utilisation of a digital platform for citizenship registry and citizenship documentations such as the issuance of birth certificate and single identity number;

- enhance cooperation with UNHCR in handling refugees and asylum seekers

- to work with all countries, particularly the two Statelessness Conventions, to learn together, increase capacities, and exchange technology in addressing statelessness.