1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis Provisions

The citizenship laws of Brunei Darussalam (Brunei), stipulated by the Brunei Nationality Act, operate largely through jus sanguinis structure and contain both racial and gender discriminatory provisions. Persons born in Brunei who “are commonly accepted as belonging to one of seven ‘indigenous groups of the Malay race’” are automatically considered citizens of Brunei if their father or both parents are citizens of Brunei. Further, children born outside of Brunei to a father who was born in Brunei and belonged to one of the seven Indigenous groups are considered citizens. Children who have both a father and mother born in Brunei who are members of one of an additional 15 ethnic groups ‘considered to be Indigenous’ to Brunei are considered citizens of Brunei whether they were born in or outside of the country. There is no definition of a stateless person or explicit mentioning of a stateless person in the citizenship legislation of Brunei.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

A naturalization process is available to non-citizens in Brunei. In order to be eligible, one must have resided in Brunei for at least twenty of the twenty five years prior to application as well as continuously for the two years immediately prior to the application, among other requirements. Any time in which a person is residing illegally in Brunei will not count towards their years of residence. Stateless persons may make an application for citizenship if they were born in the country and have been resident for at least twelve of the last fifteen years and pass a test of Malay culture and language. However, stateless persons in Brunei have reported waiting five to ten years after passing the culture and language test without gaining citizenship. An ethnic Chinese applicant stated that they waited 12 years after passing the citizenship test to receive citizenship.

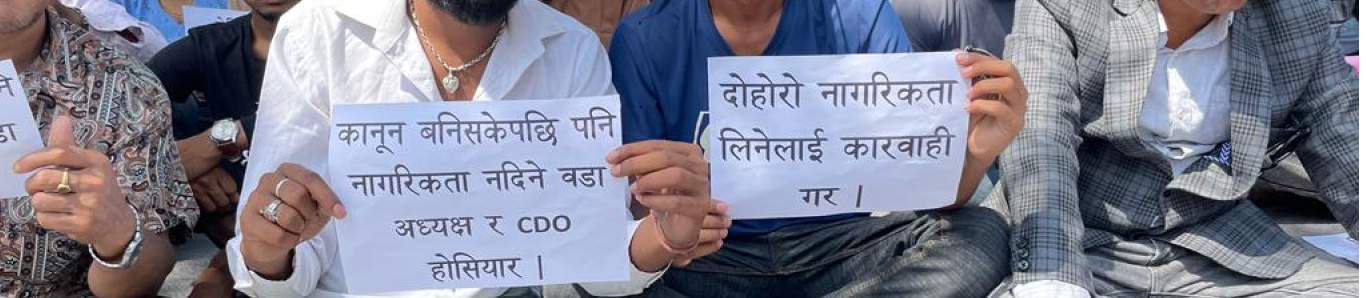

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in Brunei as a citizen who voluntarily acquires citizenship of another state will “cease to have” Brunei citizenship. If a woman who is a Brunei citizen acquires a foreign nationality through marriage, she will cease to have Brunei citizenship. There exists no provision stipulating the same for Brunei citizen men.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

Brunei has notably low rates of treaty ratification, being one of the two countries in Southeast Asia to be party to two or fewer of the relevant treaties. The two relevant treaties ratified by Brunei are the CRC and CEDAW. The country has yet to ratify the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, the ICCPR, ICESCR, and ICERD.

While a party to CEDAW, Brunei maintains reservation to Article 9(2) of the convention which provides women with equal rights regarding the nationality of their children. The CEDAW Committee has called on Brunei to withdraw its reservation and to amend the citizenship laws of Brunei to provide women the equal right to transfer their nationality to their children.

In 2016, the CRC Committee in its concluding observations to Brunei expressed concerns over the persistence of discrimination against certain groups of children, including stateless children. The Committee also pinpointed the issue of access to citizenship for children born to Bruneian women married to foreign nationals who can currently only access citizenship by application, while children of Bruneian fathers in the same situation are granted automatic citizenship. Echoing the CEDAW Committee’s concluding observations, the CRC Committee also recommended that Brunei amend the Brunei Nationality Act to ensure Bruneian women equal rights to confer citizenship to their children as well as “strengthen measures to naturalize stateless children”. Further, the CRC Committee identified that there is a lack of disaggregated data available for stateless persons in Brunei, including stateless children. The Committee encouraged Brunei to ensure universal birth registration, especially for stateless families and children, to be able to access basic rights. Regarding birth registration, the Committee also expressed its concern over the “considerable disparities in birth registration in rural and urban areas, and that children in migration circumstances, including irregular migration, as well as children in Kampong Ayer (the “water village”), are not always registered at birth”. As a party to the CRC, Brunei has committed to ensuring that every birth is registered immediately as well as that every child has the right to acquire a nationality.

It was noted in a Joint Submission of Brunei’s UPR in 2014 that there is limited engagement by civil society on statelessness in Brunei, which could be attributed to “limitations on the right to freedom of information, opinion and expression”.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunei Darussalam |