1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis Provisions

The citizenship legislation of Nepal operates through jus sanguinis provisions, which contain gender discriminatory elements. Nepal citizenship legislation is governed by both the 2015 Constitution of Nepal and the 2006 Nepal Citizenship Act which provides that a person born to a Nepali father or mother shall have citizenship by descent. Despite a provision specifically providing men and women equal rights to confer citizenship to their children, the subsequent provisions in the constitution curtail the rights of women and further categorize children based on the nationality or traceability of the father. There is no definition of statelessness included in Nepal’s citizenship law.

The Nepal Citizenship (First Amendment) Bill (2079) provided pathways for previously excluded groups to gain citizenship. Despite the President of Nepal twice refusing to sign the amendment, it was finally enacted in May 2023. While the amendment has generally ensured wider access to citizenship, it still contains gender discriminatory aspects which are discussed in greater depth below.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

Only foreign citizens who have made a significant contribution to Nepal or foreign women who have married a Nepali man can apply for naturalization. The law also states that a person born to a woman who is a citizen of Nepal and married to a foreign citizen may acquire naturalized citizenship of Nepal. There is no process of naturalization available to stateless persons or refugees.

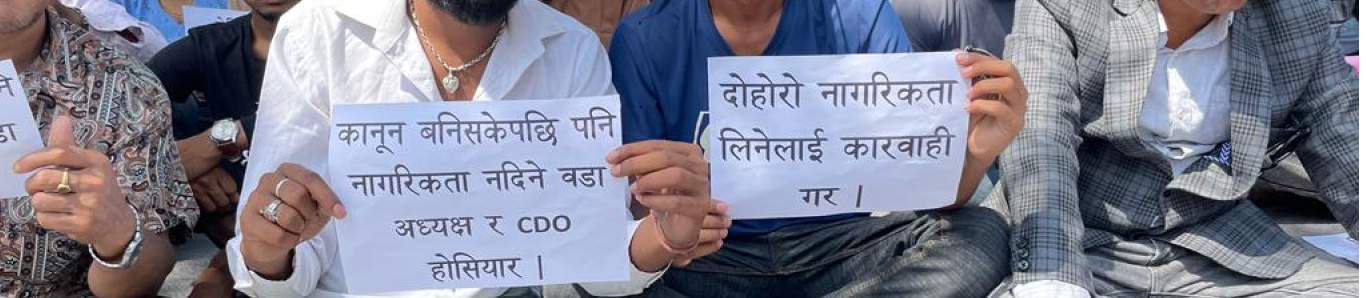

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in Nepal. A Nepali citizen who acquires another citizenship will automatically lose their Nepali citizenship. Foreign citizens applying for naturalization must first renounce their foreign citizenship, which could leave them at risk of statelessness if their application is denied and they cannot reacquire the citizenship of their former country, as there are no provisions that prevent such a situation from arising.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

Nepal has ratified ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations. However, the country has yet to ratify the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, and the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

In 2014, the CRC Committee expressed concerns regarding the low birth registration rate in the country, especially in rural areas and for women who are faced with barriers to registration. The Committee further highlighted that Nepal’s citizenship legislation includes gender discriminatory provisions and that there is no provision providing citizenship for those in Nepal who would otherwise be stateless. It was recommended that Nepal ensure universal birth registration by amending its Birth, Death and Other Personal Incidents Registration Act, establish an efficient and free birth registration system, remove barriers to birth registration and eliminate gender discrimination in its nationality legislation. These recommendations were echoed by the CRC Committee in 2016, adding that Nepal should seek assistance from UNICEF and civil society to fulfill their obligations.

The issue of Nepali women’s limited ability to confer citizenship to their children was also mentioned by the CESCR Committee in 2014. The Committee recommended awareness raising among local authorities to ensure that legislation is implemented effectively. The CRC Committee also expressed concerns in 2016 regarding the childhood statelessness of children born to a Nepali mother and foreign father who are unable to gain citizenship until they reach adulthood. It was recommended that Nepal ensure that the acquisition of Nepali citizenship by descent is accessible to children at birth.

In 2018, the CEDAW Committee also raised concern over denial of citizenship certificate and registration of children born to single mothers, which it added denies such women and their children access to bank accounts, a driver’s license, voting, managing their property, education, acquiring travel documents, applying for employment in the public sector and benefiting from social services. The Committee added that along with a high number of persons at risk of statelessness, Nepal has given no timeline for its ratification of the Stateless Conventions. Nepal was recommended to conduct citizenship certificate distribution campaigns and accede to the Statelessness Conventions. The Committee also recommended that Nepal “amend or repeal all discriminatory provisions in its [Constitution] that are contradictory to Article 9(2) of the Convention [which ensures gender equality in nationality law] to guarantee that Nepali women may confer their nationality to their children, as well as to their foreign spouses, under the same conditions as Nepali men, whether they are in the country or abroad”. In Nepal’s 2021 follow-up to the concluding observations, the country stated that “the [Constitution] ensures equality between men and women with respect to acquiring, retaining, and transferring of citizenship” and that “this also equally applies to their children”. Nepal also expressed that the “[Citizenship Amendment Bill] has also been submitted in the Federal Parliament”. In response to this, the Rapporteur stated that Nepal has yet to repeal the discriminatory provisions of the Constitution and found that the recommendation has not been implemented. While Nepal has enacted the Nepal Citizenship (First Amendment) Bill (2079) to amend gender discrimination since these concluding observations, as discussed above, remaining gender discriminatory provisions still deny Nepali women equal rights to confer citizenship.

In its 2018 concluding observations, the CERD Committee expressed concern over government officials who have reportedly discouraged Dalits from applying for citizenship. Further, it highlighted that Madheshi of the Terai region who acquired citizenship by birth prior to the promulgation of the Constitution in 2015 have not been able to confer citizenship by descent to their children, which violates article 11(3) of the Constitution. Article 11(3) of the Constitution states that “a child of a citizen having obtained the citizenship of Nepal by birth prior to the commencement of Nepal shall, upon attaining majority, acquire the citizenship of Nepal by descent if the child’s father and mother both are citizens of Nepal”. The Committee recommended that Nepal establish clear procedures for issuing citizenship certificates without discrimination, that applications are decided upon in a timely manner with written notification to the applicant of the reason for denial of citizenship, and that there be a complaint mechanism for those who receive a negative decision. With the enactment of the Citizenship Regulations in 2023, some of these concerns have been addressed.

In Nepal’s 2020 UPR submission, the country reiterated that its Constitution “ensures equality between men and women with respect to acquiring, retaining and transferring of citizenship” and that its Citizenship Act “fully recognizes and protects equal status of Nepali women while granting citizenship”. In the same session, four states (Canada, Finland, Germany and Panama) urged Nepal to amend its gender discriminatory provisions with regard to citizenship. In a joint submission for the same session, stakeholders recommended that Nepal:

- “Take all necessary measures in line with obligations under the CRC and ICCPR to grant Nepali citizenship without delay to all children residing in the State party who would otherwise be stateless, particularly children born to Nepali mothers, and implement adequate safeguards to protect all children from statelessness”;

- “Review and improve the current application process for citizenship certificates and simplify the process with a view to expediting it and making it more accessible to all applicants”;

- “Review and enhance the transparency of the system for reviewing and granting applications for citizenship and reduce the discretionary threshold for such decisions, so that citizenship certificates are granted upon meeting the relevant criteria”

- “Create a process to provide training to District Administration Offices on the provision of citizenship certificates, and establish a complaint or review mechanism in case of denial of citizenship application or discriminatory practices by civil servants”;

- “Conduct a comprehensive study on the state of statelessness of minority and lower-caste groups, and ensure that caste-based discrimination does not result in denial of citizenship”;

- “Find durable solutions for the enduring statelessness of intergenerational refugee populations in Nepal”; and

- “Accede to and fully implement the Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness”.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nepal |