1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and Jus Soli Provisions

The citizenship legislation of Bangladesh provides for both jus soli and jus sanguinis citizenship, stipulated by The Citizenship Act (1951). Under the written law of Bangladesh, persons born in the territory will gain citizenship by birth unless their father is a diplomat or an enemy alien. However, in practice, citizenship by birth appears to be provided only when a child is born in Bangladesh to two Bangladeshi citizen parents. The jus sanguinis provision of the Bangladeshi citizenship law provides that a child born either within or outside of Bangladesh to a Bangladeshi citizen automatically acquires citizenship by descent. While most gender discriminatory provisions that barred women from transferring their nationality to their children were removed by amendments in 2009, however, a few still remain in the laws of Bangladesh as women are unable to confer nationality onto their foreign spouses. If the parent of the child is themselves a citizen by descent and the child is born abroad, the birth must be registered for citizenship to be obtained. There is no definition of a stateless person nor is there explicit mention of statelessness in Bangladesh’s citizenship legislation.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

The Citizenship Act stipulates that any person can apply for naturalization in Bangladesh, the details of which are stipulated by the Naturalization Act (1926). To be eligible for naturalization, the applicant must not be a minor, must reside in Bangladesh for at least twelve consecutive months as well as for at least four of the seven years before application, and have an adequate knowledge of Bengali, among other requirements. There is no simplified or expedited procedure available for stateless persons or refugees. A foreign citizen must renounce prior citizenship upon application.

However, this provision was seen to be discriminatory in the case of Rohingyas. The Government of Bangladesh since 2014 has banned marriages between Rohingya refugees and Bangladeshi citizens in the fear of Rohingyas using marriage to obtain Bangladeshi citizenship.

Citizenship may be acquired through marriage via the naturalization process; however, the laws stipulating this include gender discriminatory provisions denying women the right to pass nationality to their spouses. However, this provision was seen to be discriminatory in the case of Rohingyas. The Government of Bangladesh since 2014 has banned marriages between Rohingya refugees and Bangladeshi citizens in the fear of Rohingyas using marriage to obtain Bangladeshi citizenship. In a 2018 Writ Petition filed, the High Court upheld the marriage ban in the case of a Bangladeshi citizen marrying a Rohingya woman. Besides Rohingyas, there is no marriage ban against any other community in Bangladesh.

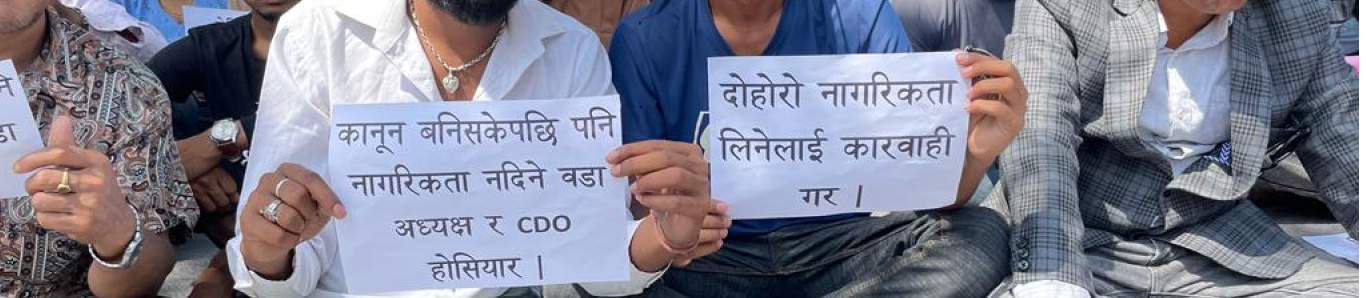

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in Bangladesh. A Bangladeshi citizen by birth automatically loses their Bangladeshi citizenship upon acquisition of citizenship of another country. However, as a result of a 1978 amendment to the 1972 Citizenship Order, there are some discriminatory provisions relating to reacquisition of citizenship based on the country of former citizens’ citizenship acquisition. Citizens of only Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States who are of Bangladeshi origin are able to apply for reacquisition of Bangladeshi citizenship.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

While Bangladesh has not yet ratified the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, or the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, it has ratified ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations.

In 2016, the CEDAW Committee highlighted that while the 2009 amendments to The Citizenship Act removed some gender discriminatory provisions, they did not retroactively apply for children before its entry into force. In regard to the lack of access to justice for women in Bangladesh, the Committee recommended that the country ensure that all women and girls, including those who are affected by statelessness, “have effective access to justice by raising their awareness of their human rights and the remedies available to claim them”.

The Committee also expressed concerns over the fact that only 3% of children born in Bangladesh are registered within 45 days of their birth and that only 88% of school-aged children were registered in 2016. Further, women and children make up a disproportionate percentage of the unregistered Rohingya population (60%). It was recommended that Bangladesh ensure that the 2009 amendments apply retroactively and ensure that all children’s births are registered immediately. The CRC Committee also recommended that the country “provide birth registration and access to basic rights, such as to health and education, for all undocumented.

However, Bangladesh has failed in its commitment to provide formal education to all children, as nearly half a million Rohingya refugee children are banned from access to formal education.

Rohingya children and their families”. As a party to CRC as well as ICCPR, Bangladesh is obligated to ensure that all births are registered immediately after birth.

In Bangladesh’s recent Universal Periodic Review, it was stated that Bangladesh has been working to ensure education for Rohingya children with the support of international organizations, including UNICEF. However, Bangladesh has failed in its commitment to provide formal education to all children, as nearly half a million Rohingya refugee children are banned from access to formal education. Further, it was stated that Bangladesh remains committed to the Rohingya population’s “right to safe, dignified and voluntary return to their homes in Myanmar”. While Bangladesh signed a repatriation deal with Myanmar and formed a Joint Working Group on the issue in 2021, Myanmar has yet to follow through in ensuring Rohingya’s right to safe, dignified, and voluntary return to Myanmar.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh |