1. Citizenship Law

Taiwan maintains its own democratic regime and provides access to nationality rights under its sovereignty. However, the Anti-Secession Law of the People’s Republic of China, enacted in 2005, asserts that “Taiwan is a part of China” and allows for the use of non-peaceful means by China to achieve unification. Taiwan’s official stance rejects this Law, asserting that “the Republic of China is a sovereign and independent state”, and emphasizes that Taiwan’s sovereignty belongs to its people. Since Taiwan does not fall under China’s jurisdiction, the Anti-Secession Law is not applicable to Taiwan. Taiwan urges the international community to support its right to exist as an independent entity in the global community.

a. Jus sanguinis and jus soli Provisions

Taiwan does not hold a concept of citizenship, but rather the system works on the concept of nationality. According to the Nationality Act of Taiwan, children born to one Taiwanese parent will be a national regardless of their birthplace. Nationals are afforded different rights based on whether they do or do not hold ‘Household Registration’, as stipulated by the Immigration Act. Those individuals who hold a ‘Household Registration’ have access to complete residential and voting rights in Taiwan. The Immigration Act was amended on January 1, 2024, making the process of acquiring nationality to those with Taiwanese parents easier. The new rules provide that for those individuals born in Taiwan to at least one Taiwanese parent and left the country without Household Registration or those individuals born overseas to a parent who holds Household Registration are allowed to immediately register upon entry into Taiwan with a valid R.O.C. (Taiwan) passport and do not need a Taiwan Area Residence Certificate (TARC).

In the Enforcement Rules of the Nationality Act, Article 3 defines a stateless individual as, “a person who is not recognized as the citizen of any country according to the laws of that country”. It also, in particular, recognizes individuals from India, Nepal, Myanmar, Thailand, and Indonesia as stateless if they conform with Article 16 of the Immigration Act and hold an Alien Resident Certificate, prescribing them as stateless.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

Foreigners and stateless persons can apply for naturalization in Taiwan if they currently have residence in Taiwan, have legally resided in the territory for at least 183 days of each year for five consecutive years and have “enough property or professional skills to support themselves”, among other requirements. Those applying for naturalization would have to renounce any prior citizenship they hold within one year after the approval of the application. There is no simplified or expedited naturalization procedure available to stateless persons or refugees, with PRC nationals having no access to naturalization at all. Foreign spouses in Taiwan are free to apply for residency or naturalization if they are married to a Taiwanese individual. Recent amendments, effective from January 1, 2024, have allowed for foreign spouses (and their minor children) married to Taiwanese nationals to obtain legal residency in the country. This is applicable without individuals having to go through judicial proceedings to obtain an official judgment of divorce or child custody to meet the residence grounds stipulated in Article 31. With these amendments, while the implementation is yet to be seen, foreign spouses who have divorced or been widowed are likely to have increased eligibility for naturalization as legal residency is a prerequisite of naturalization.

The Immigration Act of Taiwan applies to stateless persons as well as foreign individuals who have entered Taiwan with a foreign passport. Stateless individuals from Thailand, Myanmar, Indonesia, India, or Nepal or nationals without Household Registration who cannot be repatriated are permitted to reside in Taiwan. Upon the completion of a minimum of three years or 270 days each year in case of five years, or 183 days in case of seven years of their residence in Taiwan, individuals are permitted to apply for Permanent Residency, which is a requirement for naturalization. The historical reasoning behind this provision is to provide residence to Chinese diaspora coming to Taiwan from Thailand, Myanmar, and Indonesia. In light of the 2008 Tibetan uprising, the 2009 Immigration Act extended the special type of residence to stateless persons coming from India and Nepal. In other words, the provision was not enacted with the intention to provide legal status to stateless people in general but is limited to individuals of Chinese descent present in the selected countries.

Prior to the 2024 amendments in the Immigration Act, ‘foreign brides’ from Southeast Asia and mainland China had largely been excluded from naturalization in Taiwan. Before changes were made to the Nationality Act in 1999, the only foreigners allowed to naturalize in China were foreign women, who through patriarchal values were deemed to play a role in continuing Taiwanese ‘blood’. The increase of immigrant women in the country as a result caused the government to add barriers for foreign brides to acquire citizenship. In order to apply for naturalization, a foreign woman married to a Taiwanese man must undergo medical examinations, reside in Taiwan for a defined time period, renounce their foreign citizenship, pass Chinese language proficiency exams, and prove their financial security. The financial requirements of the application process used to present a major barrier for ‘foreign brides’ applying for naturalization. This has, however, been amended by the 2016 Act, where financial self-sufficiency is not required for naturalization based on marital relations. Further, according to the 2016 amendments in the Nationality Act, while it does provide for nationality to foreign spouses through naturalization, the concerned individuals shall be prone to statelessness if found undertaking a fraudulent marriage or adoption.

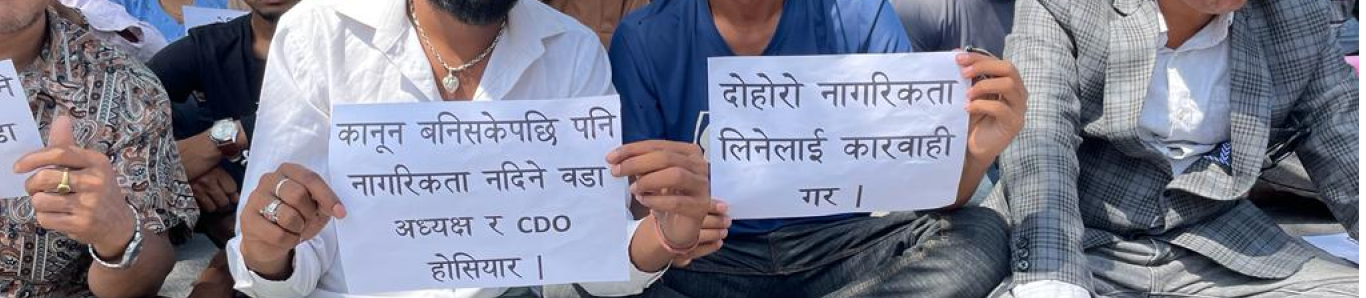

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is permitted in some cases in Taiwan. Initially, only Taiwanese citizens by birth were allowed to hold dual nationality as well as public office. Through the 2016 amendment in the nationality law, foreign nationals can now apply for dual citizenship in Taiwan, if they have made “special contributions to Taiwanese society” and are “high-level foreign professionals” in fields including technology, economic matters, education, culture, or the arts, allowing them to participate more wholly in the civic and political life. Naturalized citizens do not have access to such rights, according to the Nationality Act. Those foreign citizens, who do not fall under the narrow categories mentioned above and wish to apply for naturalization in Taiwan must provide a certificate of loss of previous nationality within one year of being approved for naturalization in Taiwan. If they fail to do so, their naturalized citizenship will be revoked.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

With Taiwan’s sovereignty being contested, the State has a limited role in the UN considering only sovereign States can become members of the UN. Taiwan has also not attained observer status. While observer status would allow Taiwan to contribute to the international system, it would also confirm that Taiwan is not a sovereign country. However, Taiwan has been seen to robustly participate in the UN specialized agencies for the last 50 years, which shows its commitment and the meaningful contribution made by it to the UN System. Despite being unable to be reviewed by UN bodies, Taiwan has created its own unique way of reviewing treaty bodies, in particular ICCPR and ICESCR, and has adopted them into its local laws since 2009. It has also voluntarily accepted other major human rights treaties, including ICERD, CEDAW, CRPD, and CRC. To maintain the credibility of the review, Taiwan invited independent international experts to conduct the reviews and has increased participation to enhance the voices of local stakeholders, such as CSOs and government officials of Taiwan.

The International Review Committee (IRC) in its 2022 concluding observations reiterated its concern about children of foreign and undocumented migrants facing statelessness. It asked the government to look into problems of “acquisition of identity documents, residency rights and/or access to basic services”, keeping in mind the child’s best interest. Caution was further displayed by the IRC in the concluding observations for CEDAW by noting the lack of help for non-national mothers with stateless children by the government, particularly social and healthcare services. The Report urges the government to provide data on the number of stateless children in the country and the services being provided to them, inclusive of healthcare, education, family, among others.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republic of China |