1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus sanguinis and jus soli Provisions

The nationality laws of Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) operate through a jus sanguinis structure with a limited jus soli provision, as stipulated by the Nationality Law of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. Persons born to two North Korean parents are considered citizens. A child born to one citizen and one foreigner or stateless person who is residing in North Korea will be a citizen. For children born outside of North Korea to one North Korean citizen and one foreign citizen where the child is under 14 years of age, citizenship is granted upon the wish of the parents. The child will gain citizenship if the parents or the guardian of the child fail to express their wish within 3 months from birth. If the child in this scenario is over 14 years of age, the parents or guardian may express their wish along with the child’s consent in order for the child to gain citizenship with the ultimate decision left to the child in the event of indecision of the parents. If an individual is 18 years of age, citizenship is granted upon the consent of the said individual. In order to complete this process, the parents or the individual must submit an application to the embassy in the foreign country where the child was born or, if unable to do so, in a nearby country. There is no definition of a stateless person included in the national citizenship legislation of North Korea.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

While Article 6 of the Nationality Law provides that a stateless person or citizen of another country can acquire North Korean citizenship by petition’, there are no provisions that provide more detail on such a process of naturalization.

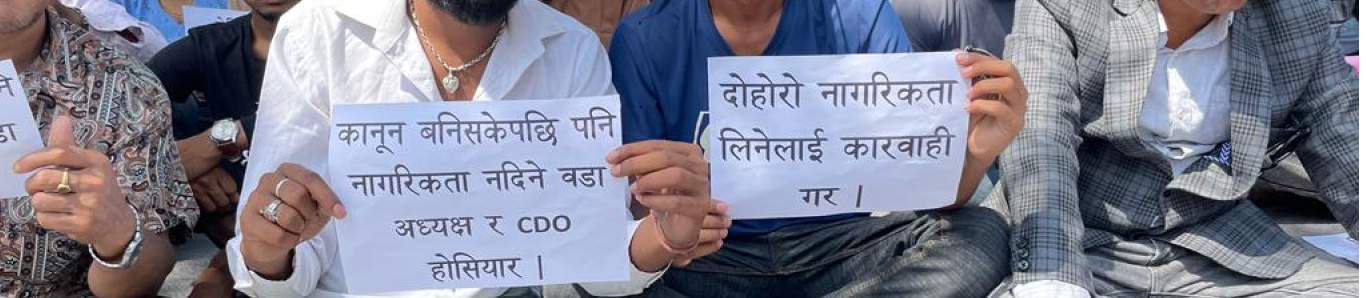

c. Dual Citizenship

The citizenship legislation of North Korea does not recognize dual citizenship.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

North Korea has ratified the ICCPR, ICESCR, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations. However, in 1997, North Korea attempted to withdraw from the ICCPR, which was rejected by the Secretary-General due to the Covenant’s lack of withdrawal provision. The country has yet to ratify the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, the 1951 Refugee Convention (and its 1967 Protocol), and the ICERD.

In its 2017 concluding observations, the CRC Committee recommended that North Korea ensure that children born to North Korean mothers outside of North Korea have access to birth registration and nationality without being forcibly returned back to North Korea. The Committee also expressed serious concerns regarding the lack of official data on stateless children in North Korea.

The CEDAW Committee in its 2017 concluding observation mentioned concerns over reports that North Korean women in China avoid registering the births of their child out of fear of being forcibly returned to North Korea, choosing instead for their child to remain stateless. The Committee also expressed concerns regarding the trafficking of women which increases the risk that they will be “subjected to forced marriage, that their children will be stateless and that they will be exploited in forced labor and prostitution”. North Korea did not provide a follow-up report to these concluding observations.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic People’s Republic of Korea |