1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus sanguinis Provisions

As Hong Kong SAR (Hong Kong) is a special administrative region of China, the region does not have its own nationality law. Instead, Hong Kong operates under the concept of “One Country, Two Systems”, enshrined under the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (Basic Law). In accordance with Article 18 and Annex III of the Basic Law, various national laws of China would apply to Hong Kong. China’s Nationality Law has applied to Hong Kong since 1997. As a result, children born in Hong Kong gain nationality through the same jus sanguinis structure, with children born within the territory to at least one Chinese parent gaining citizenship. As long as a citizen parent of a child born outside the territory has not settled abroad and the child has not gained another nationality at birth, the child will be a citizen. China’s citizenship legislation does not provide a definition of a stateless person.

Instead, Hong Kong operates under the concept of “One Country, Two Systems”, enshrined under the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (Basic Law).

b. Citizenship Law

Provisions for naturalization in China’s Nationality Law also apply to Hong Kong, with foreign nationals or stateless persons able to apply for naturalization. Foreign or stateless persons willing to abide by the constitution and laws of China, and fulfilling one of the following criteria, can apply for Chinese nationality if they are ‘near relatives’ of Chinese nationals, they are ‘settled in China’, or have ‘other legitimate reasons’. Those whose applications for Chinese nationality are approved shall be granted Chinese nationality and may not retain foreign nationality. The Ministry of Public Security will issue a certificate when applications are approved.

There are no specific rules or judicial interpretations to clarify the scope of ‘near relatives’ and the meaning of ‘settled in China’. However, based on the Application Form for Naturalization from the official website of the National Immigration Administration, close relatives include a spouse, parent, child, or sibling. While there is persistent ambiguity and no explicit specification on the meaning of “settled in China”, the Application Form includes a specified circumstance of permanent residence. Further, on China’s government website, the listed application materials required to gain Chinese citizenship include a copy of a foreign passport and a copy of the Foreigner’s Permanent Residence Card. In order to be granted permanent residence in China, one must satisfy at least one of the listed requirements, which includes but is not limited to having investments in China for three consecutive years, holding a high career title, and residing in the country for four consecutive years, or having made an outstanding contribution to and being specially needed by China. There are currently no provisions or explanations provided for what may constitute ‘other legitimate reasons’. The requirement to show a copy of the applicant’s passport in the application may act as a barrier to stateless persons who often do not have passports. There is no simplified or expedited procedure for stateless persons or refugees.

The requirement to show a copy of the applicant’s passport in the application may act as a barrier to stateless persons who often do not have passports. There is no simplified or expedite procedure for stateless persons or refugees.

As Hong Kong is a special administrative region of China, there is also a concept of “right of abode” in Hong Kong. Only permanent residents of Hong Kong have the right of abode, which provides a person with various rights, including the rights to land and stay in Hong Kong, as well as the rights to stand for election in accordance with the law. Hong Kong also has its own permanent resident status, stipulated by the Basic Law. Anyone found to be residing in Hong Kong without permanent residence may be deported from Hong Kong. The eligibility criteria for permanent residence in Hong Kong differs for Chinese and non-Chinese citizens.

Chinese citizens may be eligible to gain permanent residence in Hong Kong if born in Hong Kong, if they have ordinarily resided in Hong Kong for seven years continuously, or if they were born outside of Hong Kong to a permanent resident of Hong Kong. Non-Chinese citizens are eligible if they have legally entered Hong Kong, ordinarily resided in Hong Kong for at least seven continuous years, and have “taken Hong Kong as their permanent place of residence”. Non-Chinese citizens can also gain permanent residence if they are under 21 years of age and were born in Hong Kong to at least one permanent resident.

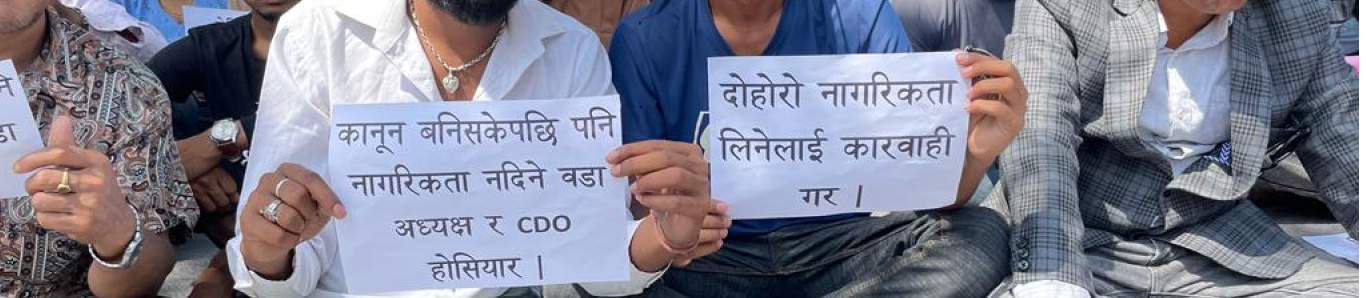

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in China, and as such, is not recognized in Hong Kong. Chinese citizens settled abroad who voluntarily acquire foreign nationality shall automatically lose their Chinese nationality. Foreigners who have previously held Chinese nationality may apply to resume their Chinese nationality if they have a proper reason to do so, while those approved to resume Chinese nationality may not retain their foreign nationality.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

While Hong Kong has yet to ratify the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness or the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, it has ratified the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons as well as the ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations. The 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons is applicable to Hong Kong as a result of Hong Kong being a British territory when Britain entered into the Convention.

Considering the potentially large number of stateless children born to refugees and asylum seekers in Hong Kong, it should be noted that as a party to the CRC, Hong Kong has committed to ensuring that every child enjoys the right to acquire a nationality. The 1954 Stateless Convention, which Hong Kong is also a party to, provides a definition for a stateless person. However, Hong Kong’s legislation does not include any such definition. Further, Article 22 of the 1954 Stateless Convention ensures that stateless persons are accorded equal treatment to nationals with respect to elementary education, which Hong Kong contravenes due to requirements of refugees, asylum seekers, and their children to periodically visit the Immigration Department, interfering with their education.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong SAR |