1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus sanguinis Provisions

The Peoples’ Republic of China’s nationality laws operate through a jus sanguinis structure. Children born within the territory of China to a Chinese national parent or parents gain Chinese nationality. Children born outside of China to a Chinese national parent or parents gain Chinese nationality unless one or both parent/s have settled abroad, and the child acquires another nationality at birth. China’s citizenship legislation does not provide a definition of a stateless person, leaving this up to the discretion of authorities.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

There is a naturalization process which is explicitly mentioned to be available to stateless persons as well as foreigners. Foreign or stateless persons willing to abide by the constitution and laws of China, and fulfilling one of the following criteria, can apply for Chinese nationality if they are ‘near relatives’ of Chinese nationals, they are ‘settled in China’, or have ‘other legitimate reasons’. Those whose applications for Chinese nationality are approved shall be granted Chinese nationality and may not retain foreign nationality. There are no provisions included in China’s legislation which details the renunciation process. The Ministry of Public Security will issue a certificate when applications are approved.

There are no specific rules or judicial interpretation to clarify the scope of ‘near relatives’ and the meaning of ‘settled in China’. However, based on the Application Form for Naturalization from the official website of the National Immigration Administration, close relatives include a spouse, parent, child or sibling. While there is persistent ambiguity and no explicit specification on the meaning of “settled in China”, the Application Form includes a specified circumstance of permanent residence. Further, on China’s government website, the listed application materials required to gain Chinese citizenship includes a copy of a foreign passport and a copy of the Foreigner’s Permanent Residence Card. In order to be granted permanent residence in China, one must satisfy at least one of the listed requirements, which includes but is not limited to having investments in China for three consecutive years, holding a high career title and residing in the country for four consecutive years, or having made an outstanding contribution to and being specially needed by China. There are currently no provisions or explanations provided for what may constitute ‘other legitimate reasons’.

The requirement to show a copy of the applicant’s passport in the application may act as a barrier to stateless persons who often do not have passports. There is no simplified or expedited procedure for stateless persons or refugees.

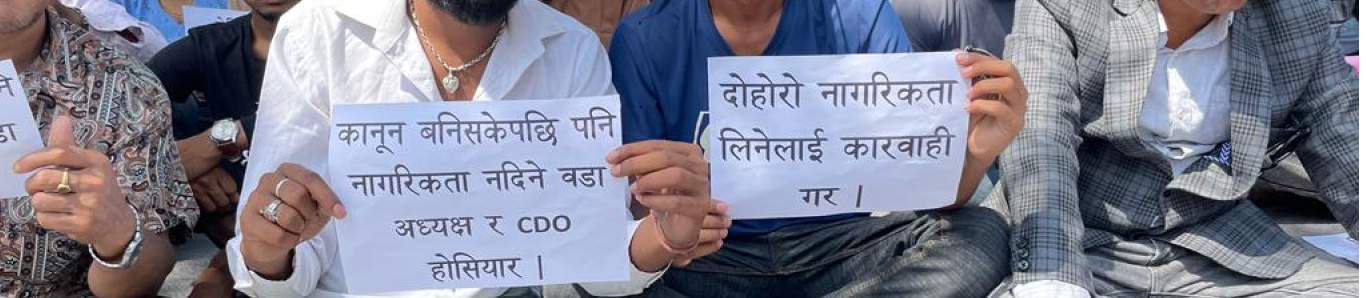

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in China. Chinese citizens settled abroad who voluntarily acquire foreign nationality shall automatically lose their Chinese nationality. Foreigners who have previously held Chinese nationality may apply to resume their Chinese nationality if they have proper reason to do so, while those approved to resume Chinese nationality may not retain their foreign nationality.

2. Treaty Ratification

While China has yet to ratify the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, it has ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, the ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations. China has also signed, but not ratified, the ICCPR.

In 2018 concluding observations, the CERD Committee expressed concerns regarding the fact that asylum seekers from North Korea are not registering the births of their children born in China, who are reportedly stateless, out of fear of facing refoulement upon registering the births. As a party to the CRC, China is obligated to ensure that all births in its territory are registered immediately as well as that no child is left stateless. Further, as a party to the Refugee Convention and its Protocol, it is further obligated to ensure non-refoulement.

Similar concerns were expressed in 2023 concluding observations by the CEDAW Committee regarding children born in China to women from North Korea, who are “deprived of their rights to birth registration, nationality, education, and health care because their birth cannot be registered without exposing the mother to the risk of deportation to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.” It was recommended that China ensure that children born to women from North Korea are eligible for citizenship and obtain birth registration. Lack of access to birth registration increases their risk of statelessness and lowers access to basic services. The 2023 concluding observations by the CEDAW Committee also noted concern regarding the “confiscation of passports from Tibetan and Uyghur women”. The Committee further recommended that China ensure that “passports are not confiscated on the basis of ethnic minority status” as well as amend nationality legislation which prohibits dual nationality.

In 2013 concluding observations by the CRC Committee, it was noted that birth registration in remote areas of China is poor “among girls, migrant children, adopted children and children whose birth would put a family above the limit of the locally “sanctioned” family size”. The Committee expressed concerns regarding family household registration (hukou), which birth registration relates to and can be a barrier for registration for children of migrant workers. It was also recommended that China abandon the hukou system to improve access to birth registration. The hukou system is a form of civil registration that also acts as the legal basis for personal identification. Children inherit the same hukou location and categorization as their parents and are not able to permanently reside or exercise a variety of rights outside of their hukou location.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People’s Republic of China |