1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus sanguinis and jus soli Provisions

The Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Citizenship of the Republic of Uzbekistan, which came into effect in 2020, is the main legislative document for citizenship in Uzbekistan. The Law contains provisions for both jus soli and jus sanguinis citizenship, and expressly states the right to citizenship. Regardless of birthplace, a child born to two Uzbek citizen parents (or a single parent) will be a citizen by descent as stated in Article 14 of the Law. Children of a stateless parent are also entitled to citizenship by descent, regardless of birthplace as long as they have one parent who is a citizen of the Republic of Uzbekistan. In instances where one parent is a citizen of Uzbekistan and the other parent is a foreign citizen, while the child is entitled to citizenship this process is not automatic and it is the responsibility of the Uzbek citizen parent to request citizenship for the child.

The Law provides that anyone who was a permanent resident in the Republic of Uzbekistan since July 28, 1992 and is not a citizen elsewhere will be a citizen of the Republic. This provision directly addresses the statelessness of many which resulted from Uzbekistan’s succession from the USSR.

In Article 3 of the Law on Citizenship, a stateless person is defined as “a person permanently residing in the territory of the Republic of Uzbekistan who is not a citizen of the Republic of Uzbekistan and does not have proof of his/her affiliation to citizenship of a foreign state”. This definition is not in line with the definition provided in the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons as it places the burden of proof on stateless persons and incorporates residency requirements.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

Stateless people in Uzbekistan can apply for naturalization in an equal manner to foreign citizens under Article 19 of the Law by attaining five years of residency with a valid residence permit, having a legitimate source of income, complying with the Constitution of Uzbekistan, and being able to communicate in the state language. It should be noted that this provision appears to require a foreign citizen to renounce their foreign citizenship, then endure five years of statelessness with a permanent residence permit in Uzbekistan before becoming eligible for Uzbek citizenship. The provision further mentions that stateless persons will still meet residency requirements if they have traveled outside of the country for no longer than 6 months each year. A simplified naturalization procedure is available for stateless persons and foreign citizens who have a “direct ascendant relative who lives in the territory of the Republic of Uzbekistan and is a citizen of the Republic of Uzbekistan”. Those with ascendant links to the country, eligible for the simplified procedure, will receive a letter of guarantee of citizenship of the Republic, valid for one year, while they renounce their foreign citizenship. This ensures that they do not become stateless in between the process of renunciation and acceptance of citizenship to Uzbekistan. Foreign citizens applying for citizenship through the standard process are not protected in this way if they are not eligible for the simplified procedure.

Additionally, the Law provides that foreign citizens and stateless persons may be granted citizenship in an exceptional manner by the President outside of the requirements set out in Articles 19 and 20. The 2020 Law also includes provisions for a simplified procedure for recognition of Uzbek citizenship for stateless persons who arrived in the country before January 1, 1995. As long as such persons do not have citizenship of another country and had residence permits (identification document for stateless persons) before the new Law was enacted, they are entitled to Uzbek citizenship and can apply through the simplified procedure for their citizenship to be recognized.

Article 22 of the Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan On Legal Status of Foreign Citizens and Stateless Persons in the Republic of Uzbekistan, ensures that stateless persons and foreigners have the right to appeal negative decisions. Uzbekistan should consider ensuring a simplified process of naturalization for all stateless persons, not just those with ascendent ties to Uzbekistan, in its territory as Article 32 of the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons stipulates that such a process should be expedited for stateless persons to “reduce as far as possible the charges and costs of such proceedings”.

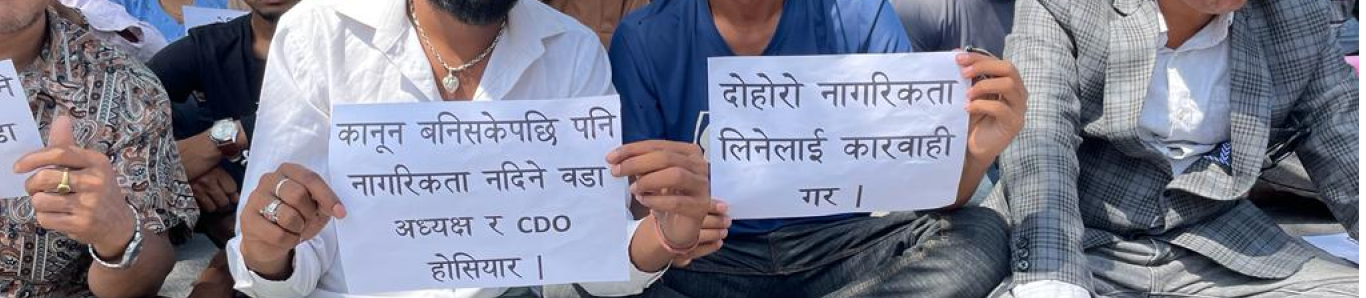

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized by the Republic of Uzbekistan Foreign citizens who do not have links to Uzbekistan through descent are required to renounce their citizenship in order to obtain citizenship of the Republic.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 1 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uzbekistan |

2. Treaty Ratification Status

Article 2 of the Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Citizenship of the Republic of Uzbekistan states that “if an international treaty of the Republic of Uzbekistan establishes other rules than those provided for by the legislation on citizenship of the Republic of Uzbekistan, then the rules of the international treaty are applied.”

Uzbekistan has ratified the ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no reservations. The country has yet to ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, or the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. Uzbekistan is the only country in Central Asia that has yet to ratify the Refugee Convention and its Protocol. Despite the fact that Uzbekistan has not yet ratified the Statelessness Conventions, much of its legislation already aligns with the Conventions, including the right to citizenship protected in the Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan on Citizenship of the Republic of Uzbekistan.

In 2020 concluding observations by the CEDAW Committee, it was recommended that Uzbekistan provide legal safeguards for its citizens living abroad who have not registered at a consulate in the last 7 years to ensure they do not become stateless.

Uzbekistan’s ratification of the ICERD binds the Republic to ensure that the right to nationality is protected. In 2020, the CERD Committee expressed concerns about the requirement for stateless persons to prove a source of income in order to apply for citizenship. The concluding observations also included concerns about discrimination faced by the Luli/Roma community, particularly the barriers they face to obtain identity documents and recommended to immediately ensure that Luli/Roma have access to such documents. To this, Uzbekistan responded as part of the follow-up procedure stating that “Lyuli/Roma persons in Uzbekistan have equal rights and equal opportunities to obtain identity documents” and that as of November 2020, 25,638 documents were issued to Lyuli/Roma persons, “including 13,100 to women”. The Committee responded to Uzbekistan’s follow-up reaffirming their concerns that only 25,638 documents were issued despite the fact that there are 69,851 Luli/Roma in Uzbekistan. Additionally, the Committee requested Uzbekistan to provide an explanation for the discrepancy in issuance of identity documents.

Further included in the concluding observations by both the CERD and CEDAW committees, are concerns regarding the lack of guarantee of Uzbek citizenship for a foreign citizen renouncing their citizenship of another state while still in the process of applying for citizenship of Uzbekistan. The CEDAW committee further expressed recommendations to ensure proper legal safeguards for children born in the territory who may otherwise be stateless and that all children born in the territory be “registered at birth and have access to Uzbek nationality and identity documents”. Uzbekistan is obligated, under its ratification of the CRC, to ensure that all children be registered immediately at birth.