1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and Jus Soli Provisions

The Law of the Kyrgyz Republic on Citizenship of the Kyrgyz Republic contains both jus sanguinis and jus soli provisions. Under Article 12 of the Law, a child, one or both of whose parents are citizens of Kyrgyzstan, is considered a citizen of Kyrgyzstan regardless of birthplace. Amendments were made in February 2023 to the citizenship laws of Kyrgyzstan removing the problematic requirements for written consent to acquire citizenship in circumstances where one parent is a foreign national. Now, in instances where one parent is a citizen of Kyrgyzstan and another parent is a foreign national, the child is considered a citizen of Kyrgyzstan unless both parents file a joint application to renounce the citizenship of Kyrgyzstan for the child who acquires another foreign citizenship at birth.

The definition of a stateless person in Article 3 of the Law on Citizenship has been amended to broadly align with the definition provided by the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons. The 2023 amendments removed the burden of proof that had previously been placed on the stateless person.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

According to the Law on Citizenship of Kyrgyzstan, to obtain naturalization, stateless or foreign persons of at least 18 years of age must attain five years of residency, proficiency in a state or official language, comply with Kyrgyzstan’s Constitution and legislation, and have a source of subsistence. However, if the person is recognized as a refugee or a stateless person in accordance with legislation by the Kyrgyz government, the period of residency required is reduced to three years. There is a simplified procedure for naturalization that removes (or reduced to one year) both the required residency period and the other requirements listed above that covers some categories of stateless persons. UNHCR has found the procedure for naturalization available to stateless persons in line with Article 32 of the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons which stipulates that such a process should be expedited for stateless persons to “reduce as far as possible the charges and costs of such proceedings”. UNHCR has recommended further simplification of the processes of naturalization including the waiving or reduction of fees and exemption for submitting certain documents.

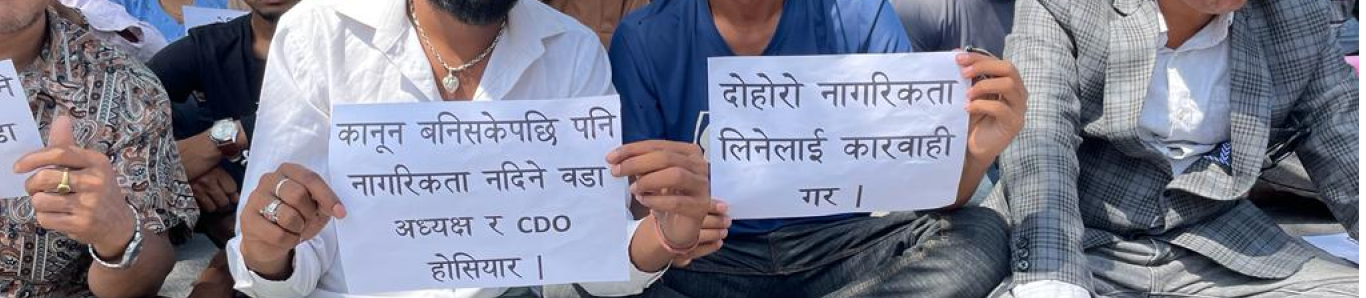

c. Dual Citizenship

While Chapter 1 of the Law of the Kyrgyz Republic of Citizenship of the Kyrgyz Republic states that dual citizenship is not recognized by the Kyrgyz Republic, except for exceptional cases and existing bilateral treaties, some forms of dual citizenship are allowed. Safeguards exist in the laws of Kyrgyzstan to protect persons from statelessness if they renounce their Kyrgz citizenship in the process of acquiring the citizenship of another state.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

While Kyrgyzstan has not yet ratified the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons or the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, it has ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, the ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW.

Under its ratification of CEDAW, Kyrgyzstan is responsible for protecting gender equality in nationality laws. In 2021, the CEDAW Committee in its concluding observations noted that issues with access to birth registration and the limited scope of the statelessness determination procedure should be amended to better ensure gender equality in implementation of nationality laws. Certain ethnic minority groups including the Lyuli or Mugat community were identified by CEDAW as facing specific barriers to accessing birth registration. On birth registration, as a party to the ICCPR, Kyrgyzstan is obligated to ensure that every child be registered immediately at birth and protect their right to acquire nationality. Included in both the recent CEDAW and CERD Committee concluding observations is a recommendation to establish a simple and streamlined statelessness determination procedure which ensures that stateless persons in Kyrgyzstan may obtain their status without discrimination. In 2021, amendments were made to facilitate more streamlined access to birth registration for children of stateless parents, providing for instances where certain documents are unable to be provided.

Under its ratification of the ICERD, Kyrgyzstan is obligated to protect the right to nationality, to work, and to equal civil rights regardless of nationality, and to ensure non-discrimination on the basis of nationality. In 2018, the CERD Committee recommended in its concluding observations to improve legal safeguards against statelessness, such as the right to appeal in Kyrgyzstan. Further, it was also recommended that Kyrgyzstan “amend the Law on External Migration to ensure that the provisions on the removal of non-citizens from its jurisdiction do not” result in discriminatory refoulement. As a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Kyrgyzstan is bound to protect the fundamental principle of non-refoulement. Expulsion of a stateless person should only be legally permitted in exceptional circumstances, of which Kyrgyzstan has overstepped in its legislation.

Kyrgyzstan has also ratified the Convention on Legal Aid and Legal Relations in Civil, Family and Criminal Cases (‘Minsk Convention’), which marks its obligation to ensure the right to a nationality, the right to change nationality, and freedom from arbitrary deprivation of nationality. However, only four States have ratified this Convention thus far.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyrgyzstan |

3. Kyrgyzstan’s Pledges to End Statelessness

At the High-Level Segment on Statelessness in October 2019, Kyrgyzstan made four pledges on statelessness. By the end of 2020, Kyrgyzstan pledged to regulate the statelessness determination process as well as ensure that all children in Kyrgyzstan have a birth certificate. Kyrgyzstan also pledged to bring its laws on birth registration in line with international standards to ensure all children are registered immediately at birth. Finally, Kyrgyzstan pledged to “study the experience of other State parties to the 1954 and 1961 Conventions on Statelessness”.

While Kyrgyzstan did not fulfill their pledges to regulate statelessness determination, provide all children with a birth certificate, or bring its legislation on birth registration in line with international standards by 2020, in 2023 UNHCR has lauded Kyrgyzstan for their subsequent actions towards reaching these aims. Amendments to citizenship laws and new legislation came into force in 2023 which ensures that no child will be left behind in birth registration and provide far greater safeguards to stateless children in their territory. However, due to the recency of these laws the success of their implementation cannot be commented upon yet.