1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and Jus Soli Provisions

While there are many strong legal safeguards in national legislation across Central Asia, not all legislations align with the Statelessness Conventions’ guidelines to eliminate the risk of statelessness. The citizenship legislation of all countries in Central Asia operates through a mixed jus sanguinis and jus soli structure. In Kyrgyzstan, children born to one citizen parent will be a citizen regardless of birthplace. In Uzbekistan, to confer citizenship to a child born to one citizen parent and one foreign citizen parent – regardless of birthplace – the Uzbek citizen parent must request citizenship for their child. While Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan also only require one citizen parent to confer citizenship, there is differential treatment between children born within or outside of the country. Children born outside of Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan must have at least one parent with permanent residence to be a citizen. In all countries of Central Asia, a child born to two citizen parents will be a citizen regardless of birthplace.

In Kyrgyzstan, as a result of 2023 amendments to citizenship laws, jus soli provisions provide automatic citizenship for children born to a stateless parent or parents. In Turkmenistan, children born to two stateless parents will only be a citizen if one parent has been habitually residing in the country. For children born to stateless parents in both Kazakhstan and Tajikistan, to access citizenship both parents must have permanent residence. There are no extra conditions placed on children born to two stateless persons in Uzbekistan, resulting in automatic citizenship at birth for these children. However, children born to one stateless parent and one foreign parent will not be a citizen in Uzbekistan. In Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, a child born to one stateless parent and one citizen parent will be a citizen regardless of birthplace. Further, children born to two foreign citizens in Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan will be a citizen if not guaranteed citizenship elsewhere.

The definitions of a stateless person in the national citizenship legislation of Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan do not align with the definition provided by the 1954 Convention, which determines status of a potential stateless person by referring to national legislation on citizenship of the country the person has or had ties with. All but Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan define stateless persons in such a way that places the burden of proof on the stateless person to prove their lack of nationality. Tajikistan’s Constitution defines a stateless person as ‘a person who is not considered a citizen of any state in accordance with its legislation,’ which is in line with the definition included in the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons. Kyrgyzstan’s 2023 amendments to citizenship laws changed its definition to remove the burden of proof and bring the definition in line with the 1954 Convention.

b. Naturalized citizenship

For all countries in Central Asia, permanent residence in the country is required for five years prior to submitting an application for naturalization. There is a simplified or expedited process of naturalization available for stateless persons in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan; however, Uzbekistan only allows this simplified process for stateless persons who are direct descendants of an Uzbek citizen. In Tajikistan, stateless persons may apply for naturalization at half the required period of permanent residence (two and a half years). In Kyrgyzstan, an expedited and simplified naturalization process is accessible for stateless persons and refugees. There is no simplified or expedited procedure available to stateless persons in Kazakhstan or Turkmenistan. For stateless persons in both Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, the documentation required to apply for naturalization may be a barrier.

In Kazakhstan, stateless persons must provide documentary proof of absence or termination of citizenship of another state in order to gain permanent residence status, which is a prerequisite for naturalization. However, many forms of such documentation are not accepted by the Republic. Kyrgyzstan also requires extensive documentation to prove stateless status and attain permanent residence status before applying for naturalization.

Article 32 of the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons stipulates that the naturalization process for stateless persons should be expedited “to reduce as far as possible the charges and costs of such proceedings.” UNHCR recommends that, in order to expedite the process and align with the 1954 Convention, the requirement of permanent residence should be removed from the process of naturalization for stateless persons.

| Conditions | Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Tajikistan | Uzbekistan | Turkmenistan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child born in the territory to one citizen parent & one stateless parent | also applies to children born in this scenario outside the country | ||||

| Children born to stateless parent(s) | parents must have permanent residence | parents must have permanent residence | one parent must be habitually resident | ||

| Children born in the territory to two foreign citizen parents (where they would otherwise be stateless) | if not granted citizenship elsewhere | ||||

| Children born to one stateless parent, one foreign parent | only if born in the territory | only if born in the territory | |||

| Foundlings | but may have to go through application process | ||||

| Children who would otherwise be stateless |

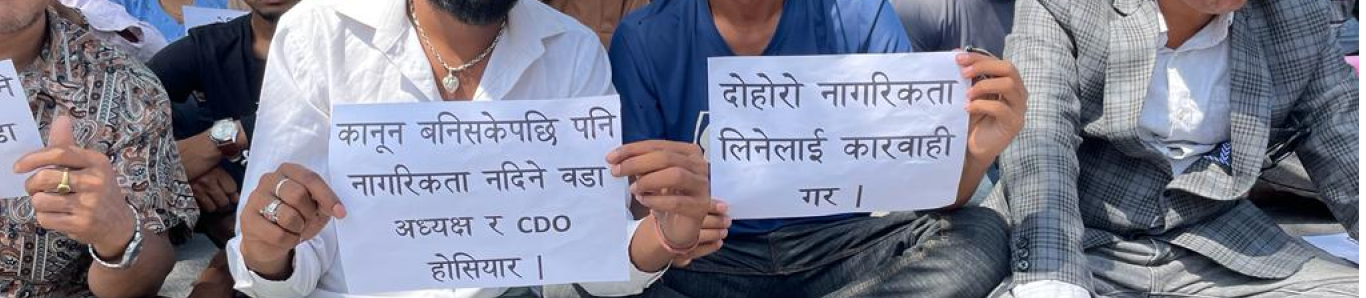

c. Dual citizenship

Dual citizenship is generally not permitted in any country of Central Asia. In Tajikistan, a person applying for citizenship must first renounce their prior citizenship, leaving people in this process at risk of statelessness. There are no provisions stipulating the process of renunciation in the citizenship legislation of Kazakhstan or Turkmenistan. Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan provide some safeguards against statelessness in the process of renunciation of prior citizenship in order to gain new citizenship. However, in Uzbekistan these safeguards are only for descendants of an Uzbek citizen, who will receive a letter of guarantee of citizenship for one year during which they must renounce prior citizenship. This ensures that they do not become stateless in between the process of renunciation and acceptance of citizenship to Uzbekistan. These same protections are not applied for foreign citizens in Uzbekistan. Article 7(1)(a) of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness states that State parties which allow renunciation of citizenship must ensure that “such renunciation shall not result in loss of nationality unless the person concerned possesses or acquires another nationality”.

Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan provide some safeguards against statelessness in the process of renunciation of prior citizenship in order to gain new citizenship. In Uzbekistan these safeguards are only for descendants of an Uzbek citizen, who will receive a letter of guarantee of citizenship for one year during which they must renounce prior citizenship. These same protections are not applied for foreign citizens in Uzbekistan.

2. Treaty ratification status

All countries in Central Asia have ratified the ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW. Uzbekistan is the only country in Central Asia that has yet to ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. Turkmenistan has the highest ratification rate in the sub-region and is the only country in the sub-region to ratify both the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. Despite the fact that Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan have not yet ratified the Conventions on statelessness, much of their legislation already aligns with the Conventions, including the right to citizenship protected in the citizenship laws of both countries. Two States in Central Asia, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, are parties to the Convention on Legal Aid and Legal Relations in Civil, Family and Criminal Cases (‘Minsk Convention’), which includes provisions binding State parties to ensure the right to a nationality, the right to change nationality, and freedom from arbitrary deprivation of nationality. However, only four States globally have ratified this Convention thus far.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | ||||||||

| Kyrgyzstan | ||||||||

| Tajikistan | ||||||||

| Turkmenistan | ||||||||

| Uzbekistan | ||||||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |