1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus sanguinis Provisions

The nationality law in Mongolia operates on a jus sanguinis basis. The Law of Mongolia on Citizenship stipulates that regardless of birthplace, a child born to two Mongolian citizen parents will be a citizen. A child born in the territory of Mongolia to one citizen parent and one foreign citizen parent will be a citizen. However, if the child is born outside the territory, the child will only gain citizenship upon written agreement from the parents. There is also no definition of a stateless person included in the citizenship legislation of Mongolia.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

A naturalization process is available to foreign citizens and stateless persons alike in Mongolia. To be eligible, one must permanently reside in the country for five years and understand the customs and official language of Mongolia, among other requirements. In order to gain citizenship by naturalization, a foreign citizen must first renounce their prior citizenship unless the other nation’s legislation stipulates the loss of citizenship upon acquisition elsewhere. There is no simplified or expedited process for stateless persons or refugees.

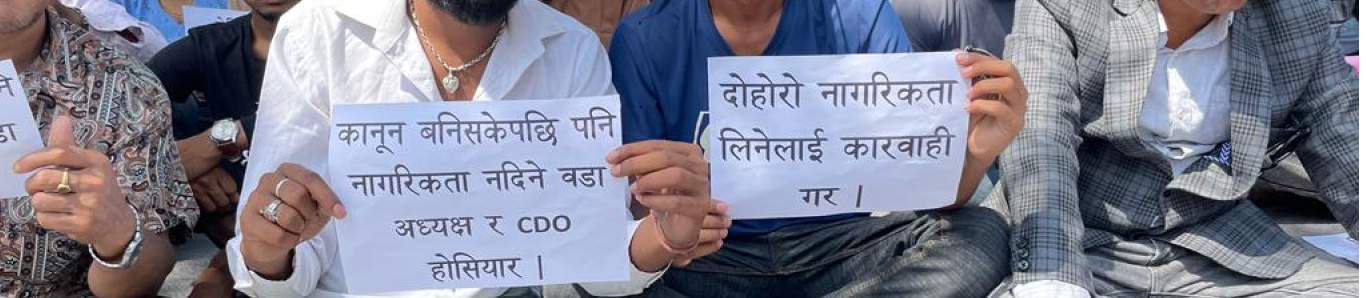

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in Mongolia, as per the Law of Mongolia on Citizenship. However, applicants in the process of naturalization are still at the risk of statelessness due to the fact that one must first renounce prior citizenship in order to gain citizenship of Mongolia by naturalization. A lack of legal safeguards around renunciation of nationality, and the bar on dual nationality has left many ethnic Kazakhs stateless. Some individuals relinquished their Mongolian nationality to gain Kazakh nationality but were unsuccessful. Others who were successful in gaining Kazakh nationality have subsequently returned to Mongolia, renouncing their Kazakh nationality and have been unsuccessful in having their Mongolia nationality reinstated.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

While Mongolia has yet to ratify the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, and the 1951 Refugee Convention (and its 1967 Protocol), it has ratified all of the relevant core treaty bodies with no relevant reservations.

In 2022 concluding observations, the CESCR Committee expressed concerns regarding the ongoing discrimination towards asylum-seekers, refugees, and stateless persons. In previous follow-up to concluding observations, Mongolia provided that it had enacted a new law which protects these groups from discrimination; however, in practice discrimination still persists. The Committee further mentioned the failure of anti-discrimination law to cover all groups and a need to make it more robust such that it covers all grounds for discrimination and all groups that are marginalized or disadvantaged. The concern regarding discrimination towards stateless persons and other groups was also touched on in 2019 concluding observations by the CERD Committee, particularly pertaining to difficulties faced by stateless persons and other persons of foreign origin in accessing State-provided services including health care, social security and education. As a party to ICESCR and ICERD, Mongolia is bound to ensure non-discrimination, including on the grounds of nationality or legal status. The issue of lack of data collection on specific groups including stateless persons was also raised in the CERD Committee’s 2019 concluding observations. The Committee requested that Mongolia provide such data in its next periodic report on socioeconomic indicators.

While commending Mongolia’s high birth registration rate, the CRC Committee recommended that Mongolia ensure a legal identity through birth registration for “Kazakh children, those who migrate within the territory of the State party and those who were born at home or without midwife support” as well as grant citizenship to all children in the territory who would otherwise be stateless.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mongolia |