1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and/or Jus Soli Provisions

The citizenship laws of most States in Southeast Asia operate through a solely jus sanguinis structure, with Viet Nam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and Cambodia’s legislation operating through a combined jus sanguinis and jus soli structure. While operating through a jus sanguinis structure, jus soli factors also come into play in Brunei due to the distinction between children born inside or outside of the country. In Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Timor-Leste, children born to a citizen parent will gain citizenship regardless of birthplace. Laos and Singapore have jus sanguinis structures that differentiate between persons born within or outside of the country. Cambodia’s jus soli provision provides that children born in the country to parents who are both foreigners and were both born and living legally in Cambodia gain Khmer citizenship by birth. Further, children born in Thailand automatically acquire Thai citizenship under jus soli provisions unless they are born to alien parents, one of whom is a temporary resident, residing in Thailand illegally, or a diplomat. In Malaysia, abandoned children and foundlings will gain citizenship by “operation of the law”, meaning that the citizenship acquisition is automatic. Viet Nam’s jus soli provisions provide citizenship by birth to children born to one citizen parent and one foreigner where the two parents cannot reach an agreement on the citizenship for the child upon birth registration, children born to two stateless parents with permanent residence, children born to a stateless mother with permanent residence where the father is unknown, and foundling children. In Indonesia, children born to parents with an unclear citizenship status, newborn children found in Indonesia with unknown parents, and children born in Indonesia when both parents lack citizenship or their existence is unknown can also obtain citizenship by birth.

Of particular note, the citizenship law of Malaysia contains gender discriminatory provisions barring women from transferring their nationality onto their children if they are born outside of the territory of Malaysia. The citizenship law of Singapore also contains gender discriminatory provisions which limit the ability of mothers to confer citizenship onto children born in the State whose fathers are diplomats or members of foreign forces during times of war. The laws of five States (Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines (for naturalized women only), Thailand and Singapore) contain gender discriminatory provisions that limit the ability of married women to confer their nationality onto foreign spouses on the same basis as men.

The interrelation between ethnicity and citizenship is notable in Southeast Asia, specifically in Brunei, Cambodia and Myanmar. Two States (Myanmar and Brunei) have ethnically defined jus sanguinis structures. The citizenship laws of Brunei operate largely through jus sanguinis structure and contain both racial and gender discriminatory provisions. Brunei’s citizenship laws limit persons who can gain citizenship through the operation of law to persons of certain defined ethnic groups and whose father or both parents (but not mother alone) is a citizen of Brunei. Similarly, citizenship of Myanmar is defined largely upon ethnic ground, and through jus sanguinis principles, with citizenship available to those who are considered “nationals” or whose parents both are nationals and members of defined ethnic groups. Further the citizenship legislation of Myanmar is the only legislation in the Asia-Pacific that explicitly provides for two other categories of citizenship being associate citizenship and naturalised citizenship, which the government may confer on any person ‘in the interest of the State’.

Eight States out of eleven States in Southeast Asia (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Loas, Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Singapore) do not provide an explicit definition of a stateless person or statelessness in their citizenship legislation. Timor-Leste’s citizenship law does include a definition of a stateless person; however, it is not in line with the definition provided by the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons. Only two States, the Philippines and Viet Nam, provide a definition of a stateless person which aligns with the definition provided by the 1954 Convention. The 1954 Convention defines a stateless person as someone “who is not considered as a national by any State under operation of its law”, which does not place the burden of proof on the stateless person.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

While there is no simplified or expedited procedure available to stateless persons in 7 countries (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Timor-Leste), they may be eligible to apply for the standard naturalization procedure. In Brunei, stateless persons may also be eligible for the standard naturalization process. However, reports of extremely long waits to hear of decisions on citizenship (5-10 years) as well as the long required residency period (20-25 years) presents a barrier to accessing citizenship through this process. In Myanmar, stateless persons are not eligible for any naturalization process as the process is reserved only for people with a citizen parent or who have married a citizen. In Viet Nam, there is a simplified procedure of naturalization available to stateless persons who had resided in the country for at least 20 years by 2009, which waives the requirement of all identity documents for those who do not have such documentation. The Philippines provides both a simplified and expedited procedure of naturalization for stateless persons and refugees, the Rule on Facilitated Naturalization of Refugees and Stateless Persons which is the first of its kind in the world. According to Article 32 of the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, naturalization should be expedited for stateless persons to “reduce as far as possible the charges and costs of such proceedings”.

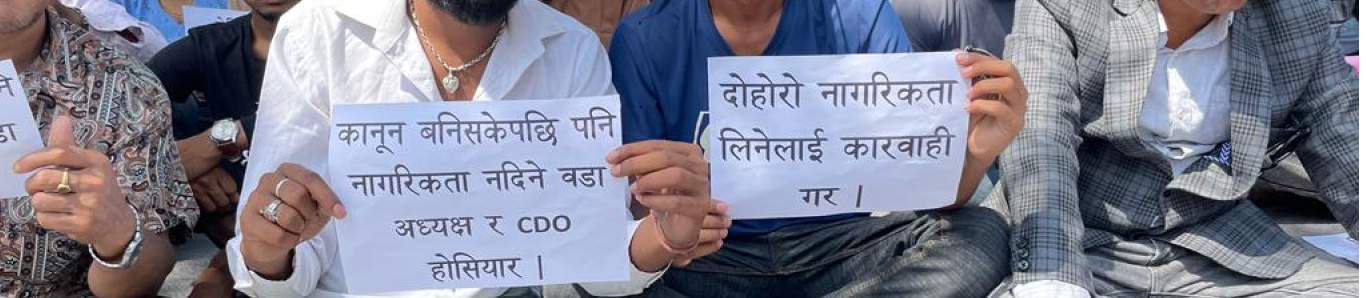

c. Dual Citizenship

Cambodia and Timor-Leste are the only States in Southeast Asia which allow dual citizenship. While 5 States (Burnei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Singapore) prohibit dual citizenship, Laos, Philippines, and Viet Nam permit it only in certain cases. Dual citizenship is generally recognized for those with jus soli citizenship in Thailand, although the law tends to be inconsistently implemented. Brunei’s legislation contains some gender discrimination in this context, as women who acquire foreign citizenship through marriage will cease to be Brunei citizens. However, the same provision does not exist with regards to Bruneian men. Foreigners applying for naturalization in Laos may have to endure an indefinite period of temporary statelessness due to the requirement to renounce prior citizenship prior to application. The renunciation process is not stipulated by legislation in Malaysia or the Philippines. The renunciation processes of all States other than Laos in Southeast Asia, where relevant, do not place persons at risk of statelessness. Article 7(1)(a) of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness states that State parties which allow renunciation of citizenship must ensure that “such renunciation shall not result in loss of nationality unless the person concerned possesses or acquires another nationality”.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

There is varied ratification of treaties across Southeast Asia, with some States — including Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines, Thailand, Timor-Leste, and Viet Nam — having very high rates of ratification, while others — Brunei, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Singapore — very low. Three States (Cambodia, the Philippines, and Timor-Leste) are parties to the Refugee Convention and its Protocol.

All States are parties to CEDAW and CRC. Brunei and Malaysia notably maintain reservation to Article 9(2) of CEDAW, which provides women with equal rights regarding the nationality of their children. Malaysia has also retained a reservation in respect to Article 7 of the CRC which provides the right to a nationality. This leaves Malaysia with minimal to no relevant international treaty-based obligations to protect or uphold a person’s right to nationality.

Eight of the eleven States in the sub-region are parties to ICESCR (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, Timor- Leste, and Viet Nam) and seven States have acceded to ICCPR (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines, Thailand, Timor-Leste, and Viet Nam). Six States (Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, the Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam) are also all parties to ICERD.

The Philippines represents a model for progressive legislation towards the prevention of statelessness in the Southeast Asia subregion. Principally, the Philippines is the only State in Southeast Asia, which is party to either of the Stateless Conventions, having ratified both the 1954 and 1961 Statelessness Conventions. The country also defines a stateless person as “a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law” in its Rule on Facilitated Naturalization of Refugees and Stateless Persons, which is directly aligned with the definition included in the 1954 Convention on the Status of Stateless Persons. It is also the only country in the entire Asia-Pacific region to have implemented a statelessness determination procedure, which it established in 2012. The Philippines also notably introduced a National Action Plan to End Statelessness in 2015 based on UNHCR’s Global Action Plan to End Statelessness. Thailand and Viet Nam have also made notable strides towards ending statelessness in their territories. Over the past decade, the Thai government has worked in partnership with UNHCR and NGOs to both expand the rights of non-citizens and to identify and provide access to citizenship for those children entitled to it. Between October 2020 and September 2021, 2,740 stateless persons were granted citizenship. Because of the exemplary work of the Thai government in identifying stateless persons, the figures of statelessness in Thailand have increased in the last five years from 443,862 in 2015 to 574,219 in 2022. Vietnam too has made significant strides towards ending statelessness by amending laws that provide for a simplified naturalization process as well as an option to reacquire Vietnamese citizenship after renunciation.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunei Darussalam | ||||||||

| Cambodia | ||||||||

| Indonesia | ||||||||

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | ||||||||

| v | ||||||||

| Myanmar | ||||||||

| Philippines | ||||||||

| Singapore | ||||||||

| Thailand | ||||||||

| Timor-Leste | ||||||||

| Vietnam | ||||||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 11 |