1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and/or Jus Soli Provisions

The citizenship laws of six out of eight States (Afghanistan, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka) operate through jus sanguinis structures. While the laws of all of these States are underpinned by the same principle of citizenship by descent, there is great variance in the structure of their laws, with many containing complex limitations on the granting of citizenship. The laws of two States (Afghanistan and Bhutan) provide an automatic grant of citizenship where a child is born within or outside of the State to two citizen parents. While the citizenship law of Afghanistan also provides avenues of acquisition for children born in the country to one citizen parent and for those born outside the country to one citizen parent with mutual consent from the parents, the law of Bhutan does not have any such provisions. The citizenship laws of two States (India and Sri Lanka) provide some differential treatment between children born within or outside of the country. Indian citizenship also operates through a jus sanguinis structure, with children born in India only considered citizens by birth if both parents are citizens of India or if one parent is a citizen of India and the other is not an illegal migrant. Children born outside of India to at least one Indian parent are considered citizens by descent so long as their birth is registered, and they are not also considered citizens of another country. Sri Lankan citizenship is provided through jus sanguinis provisions providing for automatic citizenship for children born in Sri Lanka to a Sri Lankan citizen parent. For children born outside of Sri Lanka to a citizen parent, their birth must be registered for their citizenship to be recognised.

Two States (Maldives and Nepal) with jus sanguinis structures also have discriminatory provisions in their laws that restrict the ability of conferral of nationality onto children. Nepal’s citizenship laws contain gender discrimination, while the laws of India and the Maldives discriminate on the grounds of religion. The laws of the Maldives also contain some potentially gender discriminatory provisions. Citizenship law of the Maldives operates through jus sanguinis provisions that provide automatic citizenship to a child born to a citizen of the Maldives regardless of their place of birth.

The Maldives’ citizenship legislation also discriminates on religious grounds, barring non-Muslims from being recognized as citizens of the Maldives. Conversely, India’s Citizenship Amendment Act (2019) provided a pathway to citizenship for undocumented migrants which explicitly does not apply to Muslims. The citizenship law of Nepal operates through jus sanguinis provisions, which contain gender discriminatory elements. The Nepal Citizenship (First Amendment) Bill (2079) removed some, but not all, of the previous gender discriminatory provisions. Previously, a child born to a single Nepali citizen mother would only gain citizenship by descent when the father is not identified through court order. The changes provided that children born to single mothers and citizens by birth may obtain Nepali citizenship; however, extra conditions remain for single mothers to confer citizenship to their children that are discriminatory and undignified.

Two States (Bangladesh and Pakistan) have combined jus soli and jus sanguinis structures to their citizenship laws. The laws of Bangladesh provide for both jus soli and jus sanguinis citizenship; however, in practice, citizenship by birth appears to only be provided when a child is born in Bangladesh to two Bangladeshi citizen parents. The jus sanguinis provision of the Bangladeshi citizenship law, like the Maldives, provides that a child born either within or outside of Bangladesh to a Bangladeshi citizen by birth automatically acquires citizenship by descent. The citizenship law of Pakistan operates through both jus sanguinis and jus soli provisions. Pakistan’s jus soli provisions has previously been interpreted to provide citizenship to all children born on the territory of Pakistan, except those whose fathers have diplomatic immunity, or are enemies or aliens. However, a Supreme Court decision in 2023 and a High Court ruling in 2022 both ruled that all children born in Pakistan are entitled to Pakistani citizenship by birth. Jus sanguinis provisions provide that a child born outside of Pakistan to a Pakistani citizen by birth automatically acquire Pakistani citizenship, while those born to a citizen by descent must register the birth.

The laws of three States (Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan) contain gender discriminatory provisions that limit the ability of married women to transfer their nationality to foreign spouses on the same basis as men.

None of the countries in South Asia provide a definition of a stateless person in their citizenship legislation. The 1954 Convention defines a stateless person as someone “who is not considered as a national by any State under operation of its law”, which notably does not place the burden of proof on the stateless person.

b. Naturalized citizenship

Stateless persons may be eligible for the standard naturalization process in Afghanistan. Bangladesh, Bhutan, Pakistan, and the Maldives. Bhutan’s requirements for the period of residence prior to application for naturalization are notably strict in comparison to other countries in the sub-region, requiring a residence period of 20 years prior to applying. Stateless persons have no access to naturalization in Nepal as the procedure is only open to foreign citizens, or in India due to barring individuals categorized as an ‘illegal immigrant’. In Sri Lanka, stateless persons have limited access as only stateless persons who are a descendant of a citizen, have married a citizen, or have provided distinguished service to the country are eligible for naturalization.

Bangladesh is the only country in South Asia which has gender discriminatory provisions relating to naturalization. While a foreign woman married to a Bangladeshi man may apply for citizenship through naturalization, no such provision exists which allows foreign men married to a Bangladeshi woman to gain citizenship through naturalization. India also contains discriminatory naturalization provisions on the basis of religion as only non-Muslim applicants are eligible for the expedited procedure.

None of the countries in South Asia provide a simplified or expedited procedure of naturalization for stateless persons or refugees. Article 32 of the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons stipulates that such a process should be expedited for stateless persons to “reduce as far as possible the charges and costs of such proceedings.”

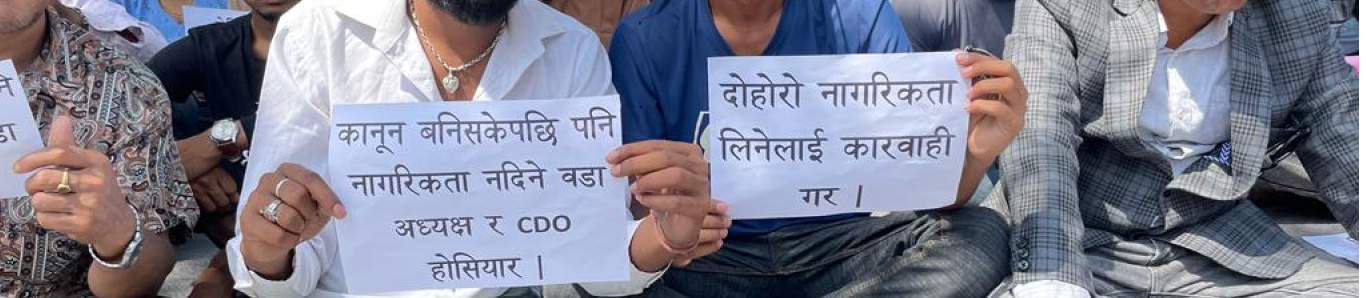

c. Dual citizenship

Only two States in South Asia, the Maldives and Sri Lanka, allow dual citizenship. In Sri Lanka, Sri Lankan citizens are required to make a declaration to the Minister in order to retain their Sri Lankan citizenship upon acquiring another citizenship. While generally not permitted in Bangladesh or Pakistan, both countries offer a list of countries with which citizens may have dual citizenship. Dual citizenship is not recognized in Afghanistan, Bhutan, India, or Nepal. In both Bhutan and Nepal, foreign citizens applying for naturalization in either country must first renounce their prior citizenship, which may place them at risk of statelessness. Article 7(1)(a) of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness states that State parties which allow renunciation of citizenship must ensure that “such renunciation shall not result in loss of nationality unless the person concerned possesses or acquires another nationality.”

2. Treaty ratification status

No country in South Asia has ratified either Stateless Convention. Only one State (Afghanistan) is a party to the Refugee Convention and its Protocol. However, there is a high rate of ratification of the key human rights treaties, with all eight States in the region party to the CRC and CEDAW and seven States (excluding Bhutan) to the ICCPR, ICESCR, and ICERD. Bhutan has signed, but not ratified the ICERD. The Maldives notably made reservations to Article 18 of the ICCPR, which ensures the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, and Article 14 of the CRC, which protects the same rights for children.

The gender discriminatory legislation of Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan contravenes the ICCPR and CEDAW, which protect gender equality in nationality laws. All three of these States are a party to the ICCPR and CEDAW. Further, India and the Maldives, due to their discriminatory provisions on grounds of religion, are not in full compliance with their obligations to the ICCPR, ICERD, or CRC as all three treaties protect the right to a nationality.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | ||||||||

| Bangladesh | ||||||||

| Bhutan | ||||||||

| India | ||||||||

| Maldives | ||||||||

| Nepal | ||||||||

| Pakistan | ||||||||

| Srilanka | ||||||||

| Total | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 |