1. Citizenship law

a. Jus Sanguinis and/or Jus Soli Provisions

All citizenship laws in the Asia-Pacific region operate through the principle of jus sanguinis, meaning that citizenship is derived via descent. The laws of eight of the 38 countries in the region additionally contain jus soli, or ‘birthright citizenship’ provisions which grant citizenship on the basis of birth on their territory (with differing limitations). Across Asia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Pakistan, and Thailand’s citizenship laws include jus soli provisions. In the Pacific, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, and Tuvalu have limited provisions for jus soli citizenship.

Of the 45 States in the region, jus sanguinis provisions in 22 States (Bangladesh, Cambodia, Fiji, Indonesia, Japan, Kyrgyzstan, the Maldives, the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Taiwan43, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Solomon Islands, South Korea, Tonga, Tuvalu, Uzbekistan, and Vanuatu) provide that children born to a citizen parent gain citizenship, with no distinction based upon the location of their birth.

In 17 states (Afghanistan, Australia, Brunei, China, India, Kiribati, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Nepal, New Zealand, North Korea, Samoa, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Vietnam) children can gain nationality where a parent is a citizen of the relevant country, however, a distinction is made between children born within or outside of the territory. For these countries while jus sanguinis is the predominant means of transferral of nationality, jus soli factors come into play.

The laws of two states (Bhutan and Myanmar) provide that citizenship may be transferred to children born within or outside of the state only if both parents are considered citizens or, in the case of Myanmar, “nationals”.

Brunei and Myanmar contain restrictions in their citizenship laws based on ethnicity. The laws of the Maldives contain provisions that limit access to citizenship based on religious grounds.

The laws of five States (Brunei, Kiribati, Malaysia, Singapore and Nepal) contain provisions that inhibit the ability of women to confer nationality to their children on the same grounds as men. Additionally, the citizenship laws of the Maldives may contain gender discriminatory provisions, however, limited information is available on the same. The laws of nine States (Bangladesh, Brunei, Kiribati, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines (for naturalized women only), Singapore and Thailand)limit the ability of married women to confer their nationality onto foreign spouses on the same basis as men. Solomon Islands also contains some gender discriminatory provisions as foreign women are required to gain the consent of their husband in order to apply for citizenship and women who have jointly adopted a child cannot apply for citizenship for their child (the father must do so).

b. Naturalized citizenship

Stateless persons are ineligible for naturalized citizenship in 7 States of the Asia-Pacific (Fiji, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Palau, South Korea, and Tonga). Due to certain requirements that are unlikely for stateless persons to be able to meet in China and Hong Kong (must provide copy of passport in application), New Zealand(being able to indefinitely reside in the country), and Kiribati (cannot be liable for deportation), stateless persons are unlikely to be eligible for naturalization in these countries. In Sri Lanka, stateless persons have limited access to naturalization as only those who are descendants of a citizen, have married a citizen, or have provided a distinguished service to the country are eligible for naturalization.

Stateless persons may be eligible for the standard naturalization procedure in 26 of the 45 States in the region (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Laos, Malaysia, the Maldives, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Mongolia, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Nauru, North Korea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu) if they meet the application requirements. However, significant barriers to meeting the application requirements exist for stateless persons in Kazakhstan (must provide documentary proof of absence or termination of citizenship of another State) and Solomon Islands (extensive documentation required) and Brunei (extremely long waits to hear of decisions). While stateless persons are not eligible for the standard naturalization process in Japan, a separate naturalization process is available for ‘aliens’.

Only 6 States in the Asia-Pacific (Australia, Kyrgyzstan, the Philippines, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Viet Nam) provide a simplified and/or expedited procedure of naturalization for stateless persons. An expedited process is available to stateless persons in Tajikistan, where stateless persons may apply for naturalization at half the required period of permanent residence (two and a half years). Stateless persons may be eligible to apply for a simplified process in Australia, Uzbekistan (only for stateless persons who are direct descendants of an Uzbek citizen), and Viet Nam. In Viet Nam, the requirement of all identity documents for those who do not have such documentation is waived for stateless persons who had resided in the country for at least 20 years by 2009. In order to be eligible for the simplified process in Australia, the only requirement is that the stateless person is not and has never been entitled to citizenship of another country. Kyrgyzstan and the Philippines provide both a simplified and expedited process of naturalization to stateless persons. In Kyrgyzstan, the simplified process available to certain categories of stateless persons removes some of the requirements of the standard process as well as reduces the required period of residency to one year or less. The Philippines has a similar progressive process available for stateless persons who have resided in the Philippines for at least 10 years, are financially stable, of good moral character, and can speak and write in one of the principal Philippine languages.

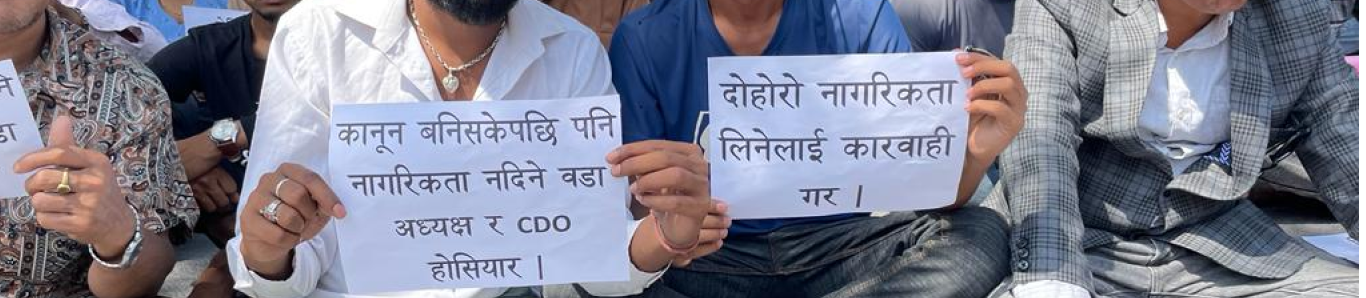

c. Dual citizenship

Dual citizenship is permitted in 10 of the 45 countries of the Asia-Pacific, including Australia, Cambodia, Fiji, the Maldives, Nauru, New Zealand, Palau, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste and Vanuatu. In 22 States (Afghanistan, Bhutan, Brunei, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kiribati, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Marshall Islands, Myanmar, Mongolia, Nepal, North Korea, Singapore, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, and Uzbekistan), dual citizenship is generally not recognized.

Dual citizenship is only permitted under certain circumstances in 13 States, including Bangladesh, Laos, Micronesia, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Samoa, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Tonga, and Viet Nam. In Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Micronesia, dual citizenship is permitted only with certain approved countries. Dual citizenship is permitted in Papua New Guinea by submission of an application, and in Sri Lanka by making a declaration. In Laos, the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand, and Viet Nam, dual citizenship is only permitted for certain groups. Only those of the Lao race who acquire citizenship by request are able to maintain dual citizenship in Laos. In the Philippines, dual citizenship is only permitted for natural-born citizens who have earlier lost their Philippine citizenship by reason of acquisition of foreign citizenship. In Vietnam, only those who are a spouse, natural parent or natural offspring of Vietnamese citizens, have made meritorious contributions to Viet Nam’s development and defense, or have outstanding talents that will be useful for Viet Nam are eligible to keep their prior citizenship after being granted naturalized citizenship. Taiwan allows dual nationality only for foreign nationals who have made “special contributions to Taiwanese society” and are “high-level foreign professionals” in certain fields. Finally, South Korea permits dual citizenship for children born to South Korean parents outside the territory of Korea, marriage migrants, naturalized foreigners of outstanding talent and those who previously held Korean citizenship.

Samoa and Tonga do not provide provisions stipulating dual citizenship in citizenship legislation. Brunei’s citizenship legislation notably contains gender discriminatory provisions relating to dual citizenship, as women who acquire a foreign citizenship through marriage will cease to be Brunei citizens. However, the same provision does not exist with regards to Bruneian men.

Where States do not allow citizenship, the process of renunciation of citizenship upon acquisition of another one (whether it be a foreign citizen applying in the country (naturalization) or a citizen of the country applying in a foreign country) may result in statelessness if there is an absence of protective legislation. For example, the laws of 10 States in the region have renunciation processes which may cause statelessness for certain individuals, including Bhutan, Kiribati, Japan, Laos, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Mongolia, Nepal, Solomon Islands, and Tajikistan. In Bhutan, Laos, Japan, Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, Mongolia, Nepal, and Tajikistan, naturalization applicants must endure an indefinite period of statelessness throughout the application process as they must renounce prior citizenship before making the application. Applicants must renounce their prior citizenship not only before the application process, but before accruing the required years of residence to be eligible for naturalization in Kiribati and Solomon Islands (for foreign spouses). For applicants to Kiribati, this means enduring 10 years of statelessness before hearing of the application’s decision. Similarly, in order for foreign women spouses of a Solomon Islands citizen to gain citizenship, they must renounce any prior citizenship and be a resident for two years before they can apply for Solomon Islands citizenship.

Where States require renunciation of citizenship upon acquisition of another citizenship, it is important to include procedural and legislative safeguards that prevent statelessness. Article 7(1)(a) of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness states that State parties which allow renunciation of citizenship must ensure that “such renunciation shall not result in loss of nationality unless the person concerned possesses or acquires another nationality”. 4 States in the Asia-Pacific (Kyrgyzstan, South Korea, Tuvalu, and Uzbekistan) do have some legal safeguards regarding the process of renunciation. However, in Uzbekistan these safeguards are only for descendants of an Uzbek citizen, who will receive a letter of guarantee of citizenship for one year during which they must renounce prior citizenship.

2. Treaty ratification status

Treaty ratification is varied and inconsistent across the Asia-Pacific. Only 7 of the 45 countries in the Asia-Pacific (Australia, Fiji, Hong Kong, Kiribati, the Philippines, South Korea, and Turkmenistan) have accessioned to the Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons(‘1954 Convention’),five of the 45 States (Australia, Kiribati, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Turkmenistan)109 to the Convention on the Reduction of Stateless Persons (‘1961 Convention’), and four to both treaties (Australia, Kiribati, the Philippines, and Turkmenistan). The region sees a slightly higher rate of accession to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees(‘Refugee Convention’),with 19 countries (Afghanistan, Australia, Cambodia, China, Fiji, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Nauru, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Samoa, Solomon Islands, South Korea, Tajikistan, Timor-Leste, Turkmenistan and Tuvalu) in the region having accessioned to the treaty and its 1967 Refugee Convention Protocol.

The key human rights treaties generally see a higher rate of ratification across the region than the Statelessness and Refugee Conventions. There is universal accession to the CRC (45 of 45 States), with Malaysia retaining a reservation with respect to Article 7 which provides the right to a nationality. Near universal accession to the CEDAW (43 of 45 States, Palau and Tonga being the two notable exceptions) exist in the region, with three States (Brunei, Malaysia, and South Korea) maintaining a reservation to article 9(2) which provides women with equal rights regarding the nationality of their children.

Over two-thirds of the States have accessioned to the other relevant human rights treaties and covenants. 32 of 45 States are party to the ICCPR (Afghanistan, Australia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Mongolia, Nepal, New Zealand, North Korea, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Samoa, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu and Vietnam).

33 of 45 States are party to the ICESCR (Afghanistan, Australia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, New Zealand, North Korea, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Solomon Islands, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Vietnam).

27 of 45 States are party to the ICERD (India, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Mongolia, Nepal, New Zealand, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Singapore, Solomon Islands, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam).

The variance between levels of ratification is notable. Three States (Australia, the Philippines, and Turkmenistan) are parties to all relevant conventions and three have ratified almost all the treaties (Fiji, New Zealand, and South Korea). In contrast, Bhutan, Brunei, Malaysia, Micronesia, Palau and Tonga can be seen to have the lowest levels of ratification. Palau has the lowest level of treaty accession of any State in the Asia-Pacific, being party only to the CRC. Malaysia, while a party to two conventions (the CRC and CEDAW) has reservations to the relevant articles that protect the right to nationality. Brunei, similarly, is a party to only two conventions (CRC and CEDAW) and retains reservations to one of those two conventions (CEDAW).