1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus sanguinis provisions

Since 1987, access to Indian citizenship has operated through a jus sanguinis structure, with children born in India only considered citizens by birth if both parents are citizens of India or if one parent is a citizen of India and the other is not an undocumented migrant. Children born outside of India to at least one Indian parent are considered citizens by descent so long as their birth is registered and they are not considered citizens of another country. The law, however, fails to provide any jus soli safeguards to children who would otherwise be rendered stateless and prevents access to citizenship, by birth or descent, to any child if either parent is an “illegal immigrant” according to the law. There is no definition of a stateless person included in the citizenship legislation of India.

Further, there has been domestic and international attention regarding the impact of the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019) which provides a pathway to citizenship for undocumented migrants of certain religions from enumerated neighboring countries. Notably, persons of Muslim faith are excluded from the operation of the Act.

b. Naturalized citizenship

Section 6 of the Citizenship Act (1955) provides for citizenship by naturalization. To qualify, an individual must renounce prior citizenship upon acceptance of naturalization to India, have resided in India for 14 years immediately preceding the twelve months before making the application, and must know an Indian language, among other requirements. India also requires reciprocity, meaning that an Indian citizen should be eligible for citizenship by naturalization in the other country in order for citizens of that country to naturalize in India. The required period of residence has been reduced to five years for persons from the Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian community from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, or Pakistan as a result of the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019). Stateless individuals are not eligible for the naturalization process, unless in exceptional cases at the discretion of the Central Government. An individual who has been categorized as an “illegal immigrant” or has renounced or been deprived of his citizenship previously also does not have access to naturalization provisions.

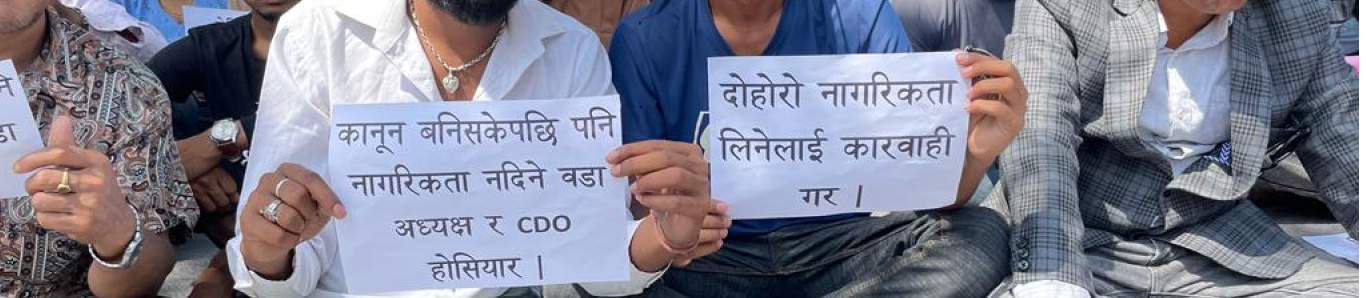

c. Dual citizenship

India does not currently offer dual citizenship. A person seeking to become an Indian citizen must renounce citizenship of another country. However, the Government of India introduced a scheme for overseas citizenship in 2006. To reduce and prevent statelessness, the Citizenship Rules (2009) provide that an individual acquiring Indian citizenship needs to renounce their foreign citizenship only once their application for Indian citizenship has been sanctioned, providing a safeguard in case their citizenship application does not get approved.

2. Treaty ratification status

While India has not yet ratified the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, or the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, it has ratified the ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations.

During its 4th Universal Periodic Review in 2019, India was advised to ratify the Conventions on Statelessness along with the Refugee Convention and take the necessary steps to implement them domestically. The recommendations also included a review of the National Register of Citizens to “avoid statelessness, deprivation or denial of nationality, arbitrary detentions or expulsions”. In the UN’s report submitted prior to the review, India was recommended to establish statelessness determination procedures to strengthen its framework for protection and assistance of stateless persons. It was also recommended that India expedite the naturalization for certain groups and extend the application of the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019) to other persecuted groups. Further, “several special procedure mandate holders called on the authorities to take resolute action to review the implementation of the National Register of Citizens and other similar processes in Assam and in other states, and to ensure that they did not result in statelessness, discriminatory or arbitrary deprivation or denial of nationality, mass expulsion or arbitrary detention”. Such arbitrary arrests and detention put India in violation of its obligations under ICCPR, which asks for a detention to not just be lawful, but also be “necessary, proportionate and reasonable.”

In 2019, the CRPD Committee expressed concern about persons with disabilities, particularly Muslim persons with disabilities, detained in camps of Assam and rendered stateless. It recommended India to adopt measures for reacquisition of nationality to those persons with disabilities rendered stateless as well as those in detention camps.

Children’s citizenship in India is determined by birth and requires at least one parent to be an Indian citizen and the other must not be an undocumented migrant. The Citizenship Act does not provide citizenship to stateless children. The Act is stated to not contain provisions explaining who it considers to be a parent or to clarify whether it includes different sets of parents of a child such as unmarried, adoptive, biological, or surrogate parents. The Citizenship Act does not cover foundlings with unknown parentage who are protected by Article 2 of the 1961 Convention which protects such children if there is no proof found to the contrary against them. While India is not a signatory to the 1961 Convention, it is a party to the CRC which requires that children be immediately registered after their birth and have a right to a nationality. The Citizenship Act is in direct contravention to India’s obligations under International Law.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India |