1. Discriminatory Laws

a. Restrictions on the Basis of Ethnicity

Ethnic minority groups across the Asia-Pacific — but largely within South and Southeast Asia — are at risk of statelessness due to discriminatory applications of citizenship laws, administrative barriers to gaining documentation and social exclusion. Notable populations include Khmer Krong communities in Cambodia, Hmong in Laos and Vietnam, ethnic minority groups living in border regions of India, Dalit and Madheshi communities in Nepal, and the sea-faring Sama Bajau in the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Discriminatory nationality laws have primarily led to statelessness among population groups in South and Southeast Asia. The most conspicuous example of ethnic discrimination in nationality laws can be seen within Southeast Asian nations. Emblematic of this is the citizenship laws of Myanmar that have rendered over a million ethnic Rohingya stateless. Population groups outside of Myanmar have also been deeply affected by ethnically discriminatory nationality laws, for example members of nine ethnic groups often referred to as ‘hill-tribe’ or ‘highland’ communities in Thailand have faced intergenerational statelessness due to discriminatory exclusion from citizenship laws. In Brunei, limitations of nationality to certain prescribed ethnic groups, or “indigenous groups of the Malay race” is the primary cause of statelessness among residents of Chinese heritage. Palau’s citizenship legislation also contains some provisions amounting to ethnic discrimination as only ethnic Palauans are able to apply for naturalization.

In South Asia, other ethnic minority groups have been historically impacted by discriminatory nationality laws which have either indirectly excluded population groups or ignored them entirely. This includes Urdu-speaking ‘Bihari’ in Bangladesh and the Mosuli and Jogi(or ‘Magat’)communities in Afghanistan.Statelessness among Muslim and ethnic minority populations in India — including persons excluded by the National Register of Citizens in Assam and Rohingya refugees —is further protracted by their discriminatory exclusion from the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019. The Maldives’ citizenship legislation also discriminates on religious grounds, barring non-Muslims from being recognized as citizens of the Maldives. As a result of previous interpretations of Pakistan’s jus soli provision, minority groups labeled as ‘alien’, including Bengali-speaking and ethnic Bihari communities, have also been denied citizenship.

b. Restrictions on the Basis of Gender

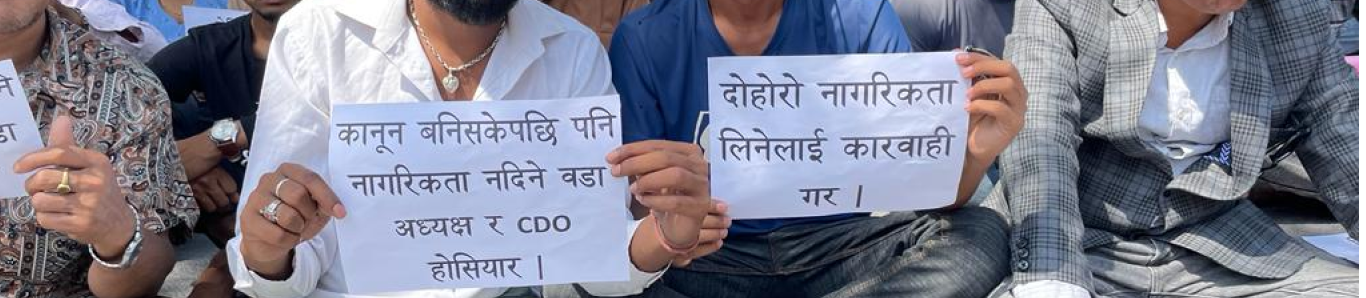

Gender discrimination in nationality laws has also played a fundamental role in creating statelessness in the region. In South Asia, Nepal’s gender discriminatory provisions restrict the ability of women to confer nationality onto their children and may have led to the statelessness of as many as 400–500,000 persons. While the laws of the Maldives also contains some potentially gender discriminatory provisions, no statistics are available on the impact of these provisions on populations in the Maldives.

In Southeast Asia, children born outside of Malaysia to Malaysian citizen mothers married to foreign fathers, as well as children born in Malaysia to Malaysian fathers and foreign mothers in an unregistered/unrecognized marriage may have been rendered stateless through gender discriminatory provisions. While there has been extensive advocacy in recent years for the amendment of these provisions, there are no available figures on the number of children affected.

Additionally, the citizenship law of Singapore contains gender discriminatory provisions which limit the ability of mothers to confer citizenship onto children born in the State “…whose fathers are diplomats or members of foreign forces during times of war”. Some gender discrimination remains in the citizenship legislation of the Philippines, as naturalized alien women who are married to Philippine citizen men may ipso facto become a Philippine citizen through marriage; however, Philippine citizen women cannot confer nationality to a foreign spouse on the same basis as men. Women are also limited in their ability to confer nationality onto foreign husbands in Brunei while Brunei men are able to confer nationality to a foreign spouse. While Thailand’s 2008 amendments to its citizenship law allowed for foreign spouses to apply for Thai citizenship without the requirement of permanent residence198, the Act still does not allow for full gender equality in the ability to confer citizenship to foreign spouses.

None of the citizenship laws of Central or East Asian States have gender, ethnic or religiously discriminatory provisions. In the Pacific, Kiribati and Solomon Islands are the only States that contain gender discriminatory provisions. Children born outside of the territory to mothers with Kiribati citizenship cannot access citizenship automatically. Citizenship by descent is limited to children whose fathers are Kiribati citizens. However, unlike other Pacific Island States, Kiribati has a small overseas population, with approximately 5,000 I-Kiribati’s living in New Zealand and Australia. There are no reliable statistics on the number of persons this provision has affected. In Solomon Islands foreign women are required to gain the consent of their husband in order to apply for citizenship and women who have jointly adopted a child cannot apply for citizenship for their child (the father must do so).

2. Lack of Legal Safeguards Against Childhood Statelessness

Legal safeguards against childhood statelessness including the protection of foundlings and children born to stateless parents are not universal across the Asia-Pacific region. The citizenship laws of less than half of the States in the region (19 States: Australia, Cambodia, Fiji, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Mongolia, New Zealand, North Korea, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu and Vietnam) explicitly provide that foundling children will be considered citizens. The citizenship laws of 12 States (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Kiribati, Malaysia, the Marshall Islands, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Thailand, Timor-Leste, and Uzbekistan) provide some/limited protection for foundling children under their law.

Underthelawsof14States(Bhutan, Brunei, China, Hong Kong, India, Federated States of Micronesia, the Maldives, Myanmar, Nauru, Palau, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu) there is no explicit protection for foundling children to gain citizenship.

Similarly, less than half of the States (14 States: Australia, Fiji, Indonesia, Japan, Kiribati, Kyrgyzstan, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Zealand, North Korea, South Korea, Timor-Leste, Tuvalu, and Uzbekistan) provide citizenship to children born on their territories who would otherwise be stateless.206 There is also limited protection provided under the laws of 17 States (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Hong Kong, Kazakhstan, Laos, Malaysia, Mongolia, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkmenistan, Samoa and Vietnam) to stateless persons born on the territory.207 However, there is no protection under the laws of the remaining 14 States (Bhutan, Brunei, India, the Maldives, Federated States of Micronesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Palau, the Philippines, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Tonga and Vanuatu).

Myanmar is the only State in the region that explicitly provides differentiated categories of citizenship (outside of naturalized/non-naturalized citizenship distinctions).

Differential treatment between persons classified as citizens by descent or citizens by birth, including limitations of citizens by descent to pass on citizenship to children exist in four States (Nepal, New Zealand, Samoa, and Singapore) in the region.

3. Citizenship Stripping

Citizenship stripping by states has wide ranging impacts across the Asia-Pacific region. In East Asia, following the end of the Second World War, and Japan’s colonial rule over the Korean peninsula approximately 52,000 ethnic Koreans were stripped of Japanese citizenship. In 2021, more than 26,000 persons and their descendants have not had their citizenship status resolved.

In both Taiwan and South Korea, foreign spouses whose marriage is determined to be a ‘sham’ or ‘fraudulent’ have been stripped of their citizenship and rendered stateless (as both states have required the renunciation of one’s former nationality prior to gaining the nationality of their spouse). This has had implications for Southeast Asian states as the majority of marriage migrants in East Asia originate from Vietnam, and have returned to Vietnam stateless following relationship breakdowns.

While not a common issue in most States of Central Asia, citizens of Uzbekistan may have their citizenship stripped for failing to register with the permanent consulate register within seven years without valid reasons while living abroad. The right to appeal is guaranteed in Uzbekistan.

In Southeast Asia (with implications in the Pacific), prior to amendment in 2006, under the citizenship laws of Indonesia persons residing outside of the territory for more than 5 years without registration were stripped of their Indonesian citizenship. This law is estimated to have affected an estimated 10–15,000 West Papuans in Papua New Guinea and at least 6,000 Indonesian migrants in the Philippines. While steps have been taken to resolve statelessness among these population groups, especially in the Philippines, thousands may remain stateless.

Within South Asia, members of ethnic Nepali communities known as ‘Lhotshampas’ living in the south of the country were stripped of their Bhutanesecitizenshipinthelate1980sandexpelled fromthecountrywithasmanyas100,000refugees arriving in Nepal during the 1990s.219 Within India, the final National Register of citizenship published in 2019 excluded 1.9 million residents from the list – essentially stripping them of their citizenship. Persons excluded from the National Register of Citizens must in turn apply to the government or foreigners’ tribunal to have their citizenship status verified, with those unable to verify their status as citizens rendered stateless. In Sri Lanka, Hill Country Tamils were indirectly stripped of their citizenship at Sri Lankan independence in 1948.

4. Administrative Barriers

Administrative barriers to accessing citizenship have rendered a vast number of populations stateless or with uncertain nationality statuses even in States across the Asia-Pacific where citizenship laws provide protection. In East Asia, the central role played by household registration in verifying one’s citizenship and realizing the associated right scan not be over stated. The impact of these systems on the realization of citizenship is specifically notable in China, Japan and South Korea among children of migrants, ethnic minority groups and those of uncertain nationalities.

Notably, within South Asia, administrative practice and policy have led to the citizenship laws of Bangladesh shifting in application from jus soli to jus sanguinis in their application. This ‘paradigmatic policy shift’ has compounded intergenerational statelessness among children born in the country, especially among the estimated 75,000 children of Rohingya refugees. Similar lack of implementation of jus soli provisions has been seen in Pakistan where children born in the country to foreigners do not automatically acquire Pakistani citizenship.

In Southeast Asia, in the past decades the provision and withdrawal of civil registration documents has been complex, discriminatory and a key component of the persecution of the Rohingya population in Myanmar. Ethnic minority groups in Brunei, Cambodia, the Philippines and Vietnam have also faced barriers to gaining civil registration and citizenship, with such barriers leading to protracted and intergenerational statelessness.

Administrative barriers to nationality appear to be less prevalent in Central Asia and the Pacific compared to areas such as East Asia where household registration plays a vital evidentiary role for citizenship, or South and Southeast Asia where exclusion from civil registration has been used as a tool of ethnic discrimination.

5. Birth Registration

In South Asia, discriminatory administrative and practical barriers have fundamentally limited the ability of women and minority groups in Afghanistan and Nepal to gain identity documentation and to confirm their status as citizens. Barriers to ethnic minority groups accessing birth registration and documentation have deeply affected populations in India and Pakistan. In the case of the ethnic Bengali population in Pakistan, such barriers have embedded statelessness for hundreds of thousands of people across generations.

The denial of civil registration documents and arbitrary and discriminatory applications of policy have played a key role in causing and compounding statelessness in Southeast Asia. For example, low birth registration rates and barriers to birth registration especially among children of migrant workers and communities living in poverty have placed as many as 50 million children in Indonesia at risk of statelessness.233 Administrative and practical barriers to accessing birth registration have placed as many as 130,000 Sama Bajau (or ‘Bajut Laut’) community members —who reside in the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia — at risk of statelessness.

Low rates of birth registration across several countries in the Pacific — notably Papua New Guinea (13%), Vanuatu (43%) and Samoa (67%)235 — place some isolated and minority groups at risk of statelessness.

While Central Asia has high rates of birth registration (with all countries reporting in the 90th percentile236), birth registration is a prerequisite for citizenship in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan and is required to obtain identity documents in Tajikistan. Due to this, for the small percentage that remains unregistered in these countries, there is a high risk of statelessness.

While all States in East Asia have high reported rates of birth registration of 100%,the central role played by household registration systems in evidencing citizenship places children of irregular migrants at risk of statelessness.

6. Requirement of Birth Registration for Citizenship Acquisition

Birth registration can help to prevent statelessness as it provides a legal record of a child’s birth place, parentage, and other key elements which determine citizenship. At the same time, a birth certifcate obtained from birth registration does not necessarily certify citizenship in all countries. Therefore, it is important to note the link between a birth certificate and citizenship certification in countries across the region to determine the risk of statelessness that may occur from incomplete national birth registration.

A birth certificate has been identified as a citizenship certifying document in 25 of the 45 States, including Australia, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kiribati, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, the Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nauru, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Viet Nam. In Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. A birth certificate certifies citizenship before a passport is issued (and up until a child reaches the age of 16 in Turkmenistan).

While a birth certificate is not explicitly listed as a document that proves citizenship in the Maldives, it is directly linked to citizenship acquisition as a child’s unique Maldivian identity number is issued upon birth registration. Birth registration in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan is not a required document for acquisition of nationality; however, children would not be able to enjoy full citizenship rights without birth registration as it is a part of the countries’ respective household registration system which determines nationality rights. While Tajikistan’s citizenship legislation does not specifically state which documents are required to certify citizenship, a birth certificate is required in order to obtain identity documents, including a passport.

| Country | Year Reported | Birth Registration Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 2015 | 42% |

| Australia | 2020 | 100% |

| Bangladesh | 2022 | 58% |

| Bhutan | 2022 | 88% |

| Brunei Darussalam | 2020 | 100% |

| Cambodia | 2022 | 92% |

| Democratic People’s Republic of Kore | * | * |

| Federated States of Micronesia | 2015 | 70% |

| Fiji | 2021 | 86% |

| Hong Kong SAR | 2022 | 90-99% |

| India | 2021 | 89% |

| Indonesia | 2022 | 81% |

| Japan | 2022 | 100% |

| Kazakhstan | 2020 | 90-99% |

| Kiribati | 2019 | 92% |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2018 | 98.9% |

| Lao People’s Democratic Republic | 2017 | 73% |

| Malaysia | 2018 | 90-99% |

| Maldives | 2017 | 99% |

| Marshall Islands | 2017 | 84% |

| Mongolia | 2021 | 100% |

| Myanmar | 2016 | 81% |

| Nauru | 2013 | 96% |

| Nepal | 2019 | 77% |

| New Zealand | 2021 | 100% |

| Pakistan | 2018 | 42% |

| Palau | 2014 | 100% |

| Papua New Guinea | 2018 | 13% |

| People’s Republic of China | * | * |

| Philippines | 2017 | 92% |

| Republic of China | ||

| Republic of Korea | 2022 | 100% |

| Samoa | 2020 | 67% |

| Singapore | 2021 | 100% |

| Solomon Islands | 2007 | 80% |

| Sri Lanka | 2009 | ≥90% |

| Tajikistan | 2017 | 95.8% |

| Thailand | 2019 | 100% |

| Timor-Leste | 2016 | 60% |

| Tonga | 2019 | 98% |

| Turkmenistan | 2019 | 99.9% |

| Tuvalu | 2020 | 87% |

| Uzbekistan | 2022 | 100% |

| Vanuatu | 2013 | 43% |

| Viet Nam | 2021 | 98% |

*No reported rates available.

**Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ birth registration rate was reported at only 77.2% in the same year.

A citizenship certifcate certifies citizenship in 5 States, including Nepal315, Papua New Guinea316, Samoa317, Solomon Islands318, and Sri Lanka319. In Afghanistan, the Tazkera, the principal Afghan identity document, proves Afghan citizenship.320 Similarly, a National ID is the main citizenship certifying document in Kazakhstan; however, to obtain a National ID, one must at least submit their birth certificate and ID of one of their parents.

In 9 States of the region (Brunei, Laos, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, North Korea, Palau, South Korea, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu), there is insufficient data to determine the link between birth registration and citizenship and no explicit mention of citizenship certifying documents in the States’ citizenship legislation. However, in Vanuatu, lack of birth registration or a birth certificate can mean that a person does not have the documentation they need to determine their citizenship eligibility.

7. Statelessness and Climate Change

As a region, the Pacific faces some of the greatest risks and has seen the greatest attention regarding the threat of climate-induced statelessness. Kiribati, the Marshall Islands and Tuvalu as low-lying States are expected to be impacted to the greatest extent from climate-induced sea-level rise. The risk of statelessness from ‘disappearing States’ currently remains a hypothetical question, with most experts agreeing that this scenario will not inevitably lead to statelessness. Before any States ‘disappear’, the impacts of relocation and an increase in displacement on communities and individual’s nationality status will need to be faced. It is this displacement across borders rather than the ‘disappearance’ of islands that poses the greatest risk of statelessness in the future. Less attention has been paid to the potential impacts of climate change on other regions in the Asia-Pacific.