1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus sanguinis and jus soli Provisions

The citizenship law of the Republic of Korea (South Korea) operates mainly through a jus sanguinis structure with one jus soli provision. According to the Nationality Act, a child born to one or two citizen parents is considered a citizen, with no distinction made regarding the individual’s place of birth. Citizenship by acknowledgement is also possible for foreign citizen children who have a citizen parent. There is no definition of statelessness or a stateless person included in the citizenship legislation of South Korea.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

Stateless persons are not included in the naturalization provisions of South Korea’s Nationality Act. However, non-citizens may gain citizenship by naturalization if they “sustain a domicile” in South Korea for at least five years, are financially independent, and have basic knowledge of Korean language and customs. Reports however suggest that the process of naturalization takes place for a prolonged period and is too difficult to obtain for stateless refugees, making their situation precarious and opening them to prolonged periods of statelessness. A simplified naturalization process is open to limited foreigners who satisfy the categories of making an outstanding contribution to South Korea, or having a parent who is a South Korean national, or whose spouse is South Korean, among others.

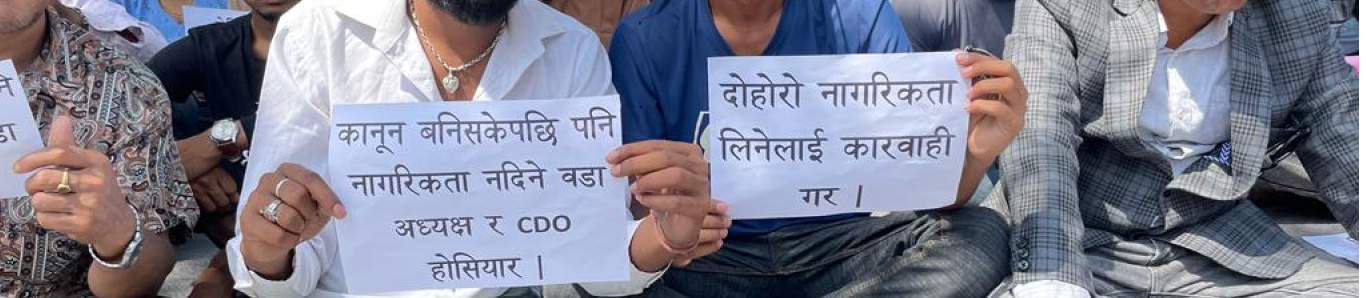

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is not recognized in South Korea. In order to gain South Korean citizenship, a person with foreign citizenship must renounce their prior citizenship within one year of receiving South Korean citizenship. A South Korean citizen will lose their citizenship upon gaining citizenship of another state. However, a 2010 amendment to the Nationality Act made an exception to this for children born to South Korean parents outside the territory of Korea, marriage migrants, naturalized foreigners of outstanding talent and those who previously held Korean citizenship. As a result of the amendment, eligible persons can maintain dual citizenship by making a pledge to the Minister of Justice not to exercise their non-South Korean citizenship while in South Korea.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

South Korea is the only state in East Asia and one of only six states in the Asia Pacific that has acceded to the 1954 Statelessness Convention. While it has not acceded to the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, it has ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW. A 2021 Mapping report of Statelessness in South Korea notes that while the Constitution of the country stipulates that international treaties should be considered part of domestic law, in practice that 1954 convention is not applied as domestic law (most notably in the lack of codified definitions of statelessness and stateless persons). Upon signing CEDAW, South Korea made a reservation stating that the country is not bound to Article 9, which stipulates gender equality in nationality. Article 9 also states that the “State Parties shall grant women equal rights with men to acquire, change or retain their nationality” and that change of nationality of the husband shall not automatically alter the nationality of the wife, “render her stateless or force upon her the nationality of the husband”. South Korea also made a reservation on Article 16(1)(g), which provides equal rights of husband and wife, particularly “to choose a family name, a profession and an occupation”.

In its 2023 concluding observations, the Human Rights Committee expressed concerns regarding the severe lack of anti-discrimination legislation, including on the grounds of nationality. Further concerns expressed by Committee is with regard to reports of pervasive hate speech towards “escapees from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Muslim migrants and refugees” as well as “towards migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, including by politicians and public figures, both offline and online”. This was echoed in 2017 concluding observations by the CESCR Committee, which found the exclusion of non-citizens from the country’s social security system and public services concerning. As a party to both of the ICCPR and ICESCR, South Korea is bound to protect the right to freedom from discrimination. South Korea did not respond to the concerns regarding discrimination on the grounds of nationality specifically in the follow-up to the CESCR Committee’s concluding observations. The Rapporteur responded that South Korea’s progress in ensuring non-discrimination on all prohibited grounds of discrimination is insufficient.

On birth registration, the Human Rights Committee in 2023 observed the issue of the requirement for foreigners to go to their respective embassy in order to register the birth of their child, making birth registration effectively unavailable for stateless persons. The issue of birth registration for foreigners was also mentioned in the CERD Committee’s concluding observations in 2019. The Human Rights Committee has recommended expediting the enactment of the bill on birth registration for foreign children in South Korea. The CEDAW Committee stated in 2019 that the children of undocumented, unmarried migrant women are at particular risk of statelessness due to administrative and legislative barriers to birth registration. As a party to both the ICCPR and the CRC, South Korea is obligated to ensure that every birth in its territory is registered immediately – not just the births of citizens. In the 4th cycle UPR submission for South Korea, it was recommended that the country “establish a universal birth registration system which includes children of refugees, asylum-seekers, stateless persons, persons of undetermined nationality and undocumented persons” as well as ensure that every birth in the country is registered immediately. In an effort to comply with the Global Compact on Migration, South Korea made a pledge in January 2023 for “introducing a birth registration system for foreign children” by December 31, 2026.

The 2019 concluding observations by the CERD Committee also included concerns regarding legislative provisions that require the passport of the mother for citizenship applications for children born out of wedlock to a foreign mother and Korean citizen father. As a result, instances where issuance of a passport to the mother is not feasible, leaves children in such a scenario unregistered. It was recommended that South Korea amend the relevant provisions to remove barriers to citizenship for children born out of wedlock to a Korean citizen father and foreign mother. In South Korea’s 2019 follow-up report to the CERD Committee’s concluding observations, it clarified its intentions by reporting its actions to draft a new bill to address issues with birth registration in the country. It also explained that for children born out of wedlock, the ‘citizenship by acknowledgement’ provision is meant to make acquisition of citizenship easier. In a follow-up report provided by a South Korean NGO Coalition, the Coalition noted that South Korea has not taken any actions to implement the recommendations provided by the Committee. The Coalition also stated that the government has previously expressed that it is unsure which branch of the government is responsible for overseeing birth registration. The Rappourter provided in its follow-up to this information that the ‘citizenship by acknowledgement’ provision does not remove all barriers to citizenship for children born out of wedlock to a foreign mother and Korean citizen father. The Rapporter further stated that the national legislation on citizenship in South Korea, contrary to the State party’s statement, does not fully protect all children from statelessness in its territory.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republic of Korea |