1. Citizenship Law

a. Jus Sanguinis and Jus Soli Provisions

Kiribati’s national citizenship legislation operates through a combined jus soli and jus sanguinis structure with an additional condition of births in or out of wedlock. Children born in Kiribati to an I-Kiribati parent are automatically entitled to citizenship. Those born in Kiribati who are not of I-Kiribati descent are automatically entitled to citizenship by birth if they are not entitled to any other citizenship. Citizenship by descent is limited to children whose fathers are Kiribati citizens. Children born outside of Kiribati to mothers who are Kiribati citizens are not able to acquire Kiribati citizenship. There is no explicit mention of foundlings or stateless children nor is there a definition of statelessness in the citizenship laws of Kiribati.

Kiribati is one of the four countries in the Asia-Pacific with gender discriminatory nationality laws that limit or inhibit the ability of women to pass on their citizenship to children. Citizenship by descent is limited to children whose fathers are Kiribati citizens. For children born in wedlock, regardless of birthplace, only the father is able to confer citizenship to the child. However, if the child is born out of wedlock, regardless of birthplace, citizenship may be conferred by either parent. Even for adoption, if the parents are married, the father must be a citizen in order for the adopted child to gain citizenship. Women who lost their Kiribati citizenship as a result of gaining citizenship from marrying a foreign citizen must apply for reacquisition of their citizenship, which is not guaranteed, placing women in this situation at risk of statelessness. Women are also unable to confer nationality to a foreign spouse upon marriage, but Kiribati citizen men are able to confer nationality to foreign wives.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

There is a naturalization process available to anyone who is 18 years old, of good character, who intends to stay in Kiribati, can speak Kiribati, and is financially independent, among other requirements. With the Citizenship Amendment Act (2022), the period of permanent residence required for the application increased from seven to ten years. Further, the Amendment Act added a new eligibility requirement, which states one must also have a permanent residence visa issued under the Immigration Act (2019) in order to be eligible for citizenship by application. In order to get a permanent residence visa, as per the Immigration Act, one must be living in Kiribati for a period of seven years and cannot be “liable for deportation”.

There are no provisions providing a simplified or expedited naturalization process for stateless persons or refugees. Kiribati’s laws on naturalization also include gender discriminatory provisions. In the applications for naturalization, men are able to include their wife and children on the application only if the wife provides written consent to the acquisition of citizenship, but there is no such provision for women to include their husbands or children in their application.

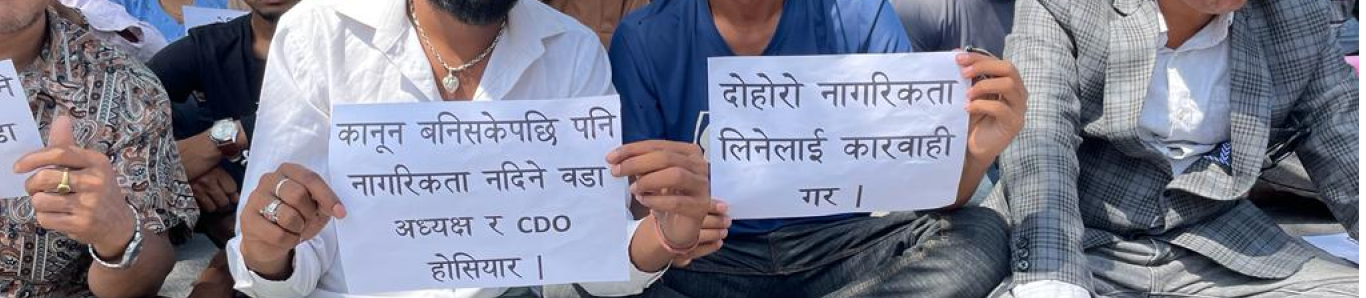

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is prohibited in Kiribati. Another eligibility requirement to apply for naturalization is to renounce any prior citizenship. Further, the period of permanent residence required for naturalization does not count until the person has renounced their citizenship. This means that in order to be naturalized in Kiribati, one must remain stateless for ten years before knowing the citizenship decision.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

Kiribati has ratified several international treaties, including the CRC, CEDAW, the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, without making any reservations. Kiribati is one of only two states in the Pacific and one of four states in the entire Asia-Pacific region to be party to both Statelessness Conventions. The Kiribati government has acknowledged the discriminatory nature of its citizenship provisions and their inconsistency with the state’s international obligations under CEDAW.

The 2022 concluding observations by the CRC Committee have recommended that Kiribati continue improving its birth registration by strengthening access to online registration, eliminating birth registration fees including late fee penalties, and combatting stigmatization of unwed mothers and their children. As a party to the CRC, Kiribati is obligated to ensure that every birth in its territory is registered immediately.

Under the 1961 Convention, Kiribati is obligated to grant citizenship to those born in the territory or outside to a citizen who would otherwise be stateless. Kiribati’s citizenship legislation does not fulfill this obligation due to discrimination based on gender for conferral of citizenship for children born in wedlock. This also breached Kiribati’s CEDAW obligation to ensure gender equality in conferring citizenship to children. In the 2020 concluding observations, concerns and recommendations were expressed by the CEDAW Committee for Kiribati to amend its laws to ensure gender equality in conferral of citizenship. Kiribati was issued a letter from the Rapporteur in March 2022 stating that the country has yet to provide follow-up to these concluding observations. There has been no follow-up from Kiribati on this to date.

Kiribati breached its obligations under the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, particularly Article 3, which regards non-discrimination in the implementation of the treaty’s provisions. This breach stems from provisions that allow men to include spouses and children in applications for naturalization without extending the same right to women. Additionally, Article 8 of the Citizenship Act needs to be amended to comply with the 1961 Convention. This provision currently does not allow citizenship deprivation for “public good,” which is considered a reasonable means for depriving someone of citizenship under the Convention.