Citizenship Law

a. Jus sanguinis Provisions

Timor-Leste’s citizenship law, stipulated by the Law on Citizenship (2002), operates through the principle of jus sanguinis, providing that children born to at least one citizen parent, regardless of birthplace, will be considered a citizen. A child born to “incognito parents”, stateless parents or parents with undetermined nationality are granted citizenship, according to Section 1(b) of the Law. There is no interpretation or definition of “incognito parents” provided in Timor-Leste’s legislation. Children born to a foreign parent who “declares to become an East Timorese national of his or her own accord” will also be citizens.

Further, the Law on Citizenship defines a stateless person as “an individual who is not able to demonstrate a legal bond of citizenship with any State”. This definition does not align with the definition provided by the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons, which determines the status of a potential stateless person by referring to national legislation on the citizenship of the country the person has or had ties with.

b. Naturalized Citizenship

Citizenship may also be acquired by naturalization in Timor- Leste. To be eligible for this process, one must “be a usual and regular resident” for at least ten years before December 7, 1975, or after May 20, 2002, as well as speak one of the official languages, among other requirements. While stateless persons may be eligible for this process, there is no simplified or expedited procedure for naturalization available for stateless persons or refugees in Timor-Leste.

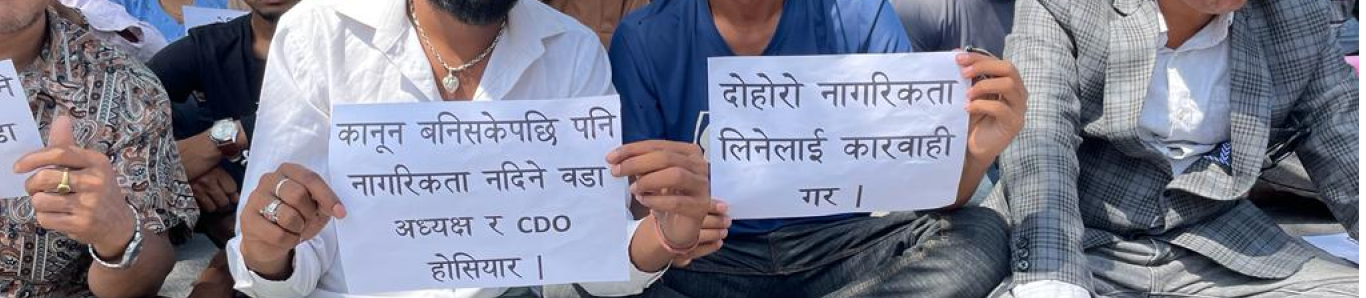

c. Dual Citizenship

Dual citizenship is recognized in Timor-Leste, as stipulated by Section 5 of the Law on Citizenship.

2. Treaty Ratification Status

While Timor-Leste has yet to ratify the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, the country has ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, ICCPR, ICESCR, ICERD, CRC, and CEDAW with no relevant reservations. In its 2023 concluding observations, the CEDAW Committee expressed concerns regarding the lack of data on stateless women and girls in Timor-Leste. In 2015, the CRC Committee highlighted the low birth registration rate, especially in rural areas, of which costs for documents remained a barrier. As a party to CRC, Timor-Leste is obligated to ensure that every birth is registered immediately and that all children enjoy the right to acquire a nationality.

In 2014, Timor-Leste committed to the principle of universal birth registration and to improve its CRVS systems. A program to fulfill this commitment was launched in 2020, which is elaborated on in the administrative barriers section.

| Country | Stateless 1 | Stateless 2 | Refugee | ICCPR | ICESCR | ICERD | CRC | CEDAW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timor-Leste |